How long have video game stores actually got left (and can they save themselves)?

Physical game sales are falling and high-street game stores face increased competition from online retailers. Is there anything they can do to stay open?

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

GamesRadar+

Your weekly update on everything you could ever want to know about the games you already love, games we know you're going to love in the near future, and tales from the communities that surround them.

Every Thursday

GTA 6 O'clock

Our special GTA 6 newsletter, with breaking news, insider info, and rumor analysis from the award-winning GTA 6 O'clock experts.

Every Friday

Knowledge

From the creators of Edge: A weekly videogame industry newsletter with analysis from expert writers, guidance from professionals, and insight into what's on the horizon.

Every Thursday

The Setup

Hardware nerds unite, sign up to our free tech newsletter for a weekly digest of the hottest new tech, the latest gadgets on the test bench, and much more.

Every Wednesday

Switch 2 Spotlight

Sign up to our new Switch 2 newsletter, where we bring you the latest talking points on Nintendo's new console each week, bring you up to date on the news, and recommend what games to play.

Every Saturday

The Watchlist

Subscribe for a weekly digest of the movie and TV news that matters, direct to your inbox. From first-look trailers, interviews, reviews and explainers, we've got you covered.

Once a month

SFX

Get sneak previews, exclusive competitions and details of special events each month!

Our Price. Tower Records. Virgin Megastore. These music-retail giants once dominated the high street, but in a few short years they were swept away in a digital apocalypse. None of them were quick enough to react to the change in consumer habits as downloads replaced CD sales, and many towns that once boasted a range of music shops were soon left with none at all.

Now it’s happening again - but this time, the battlefield is video games. Game stores have been fighting competition from internet retailers for years, but now digital downloads look set to sweep away game shops just as they put paid to music retailers in the past. The past decade has already seen multiple store closures - could the next decade wipe out the game shop for good? And is there anything that stores can do to stop it?

A lesson from the music industry

High-street music shops were the first retailers to be hit hard by the move to digital downloads and internet shopping. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry estimates that the music industry as a whole lost 40% of its revenues in the 15 years from 2001 to 2016, with physical sales dwindling every year since 2003.

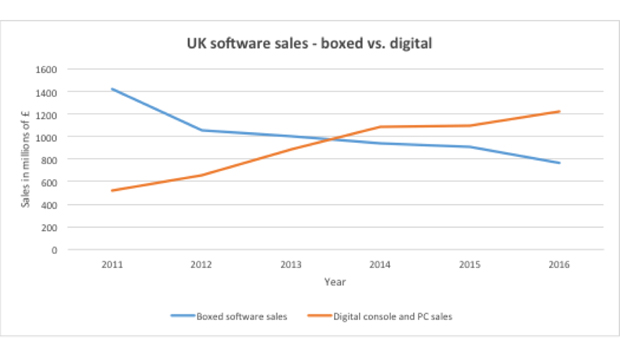

Thanks in part to their much larger file sizes in comparison to music tracks, it took longer for video games to be drastically affected by the general move towards digital downloading. But, inevitably, digital downloads are now taking the place of physical sales. MCV has reported official numbers for boxed software and digital sales since 2011, and the data shows that physical game sales in the UK have been declining steadily.

"30-40% of sales for many console games are now digital"

It seems the peak in boxed-software sales occurred in around 2008, and physical game sales have been declining ever since - even though people are actually spending more money (the total UK games market was worth a record £4.33 billion in 2016). High-street shops are finding themselves fighting it out for an ever smaller slice of the boxed-software pie.

Piers Harding-Rolls, director of research and analysis for games at IHS Markit, reckons the shift towards digital distribution will only continue: “In 2016, UK consumer spend on digital games content and services was worth 76% of the total market. This is expected to grow to 79% in 2017 and will continue with this trend over the next few years. The console, which traditionally is the last bastion of physical media sales, has started to hit a tipping point of digital sales for full-game downloads, with 30-40% of sales for many games being digital. Add in the fact that fewer AAA titles are being developed and a majority of those that are will be offered as a service, and we’re fairly rapidly heading towards even more digital distribution dominance.”

Indeed, the trend towards digital may be accelerating. A recent report from GamesIndustry.biz says that in 2017, 45% of some console titles were purchased digitally. And Activision just revealed that 50% of the sales of Destiny 2 on console were digital.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

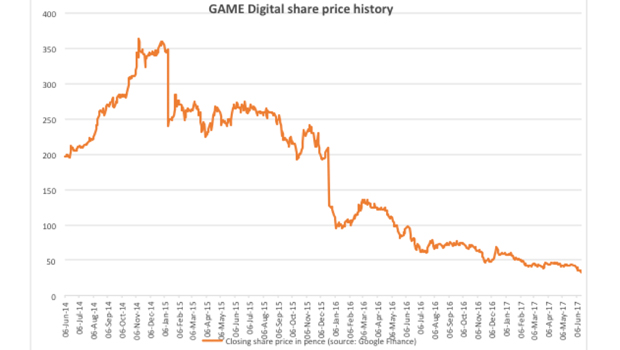

It’s not good news for bricks and mortar retailers. The UK store GAME, one of only a handful of remaining video-game chains on the high street, along with Grainger Games and CEX, already spent a spell in administration in 2012. Since the company’s shares were relisted under the name GAME Digital in 2014, their trajectory has been mostly downwards.

Paul Summers, a financial analyst at The Motley Fool, doesn’t see a bright future ahead for the company: “If you're looking for the retailing equivalent of a character from the Walking Dead, GAME fits the bill.”

Indie apocalypse

GAME may face a tough road ahead as more sales go to digital or online, but the future is even more bleak for the few remaining independent game stores. I asked indie game store owners how they’ve been affected by the rise of digital, and I was inundated with replies, all tinged with a sense of doom.

Stephen Osborne of The Game Place in Stoke-on-Trent paints a dark picture. “Earlier today I compared October 2016 to October 2017 so far. In every respect I was (within 1 or 2%) 50% down on customer numbers and sales. New sales have fallen by half, secondhand sales have fallen by two-thirds. I have been trading under my break-even point now for a very long time. The lack of cash means that some new releases can’t be stocked, and the ones that have been have not sold (either a low percentage of stock taken or none at all). The business is unable to invest into new lines or restocking items.”

"I figure I could make more money pulling funny faces outside the railway station than from digital codes. So bollocks to that."

Some indie stores have tried to sell digital codes for games or things like FIFA’s Ultimate Team in an attempt to compete with the fall in physical sales. But the profit margins on codes like this are wafer thin. Jason Hart from The Games Exchange was particularly forthright about them: “I never have done digital from the beginning and never will. The insulting margins make me feel a bit sick inside. I will go to the grave before I stock it unless margins at least treble or quadruple. I figure I could make more money pulling funny faces outside the railway station. So bollocks to that.” Stuart Benson, owner of Extreme Gamez in Ashby de la Zouch, agrees that there’s no money to be made in digital codes: “While we do digital in store, the profit isn't there and it isn't viable to continue with the brick and mortar stores like ourselves.”

Osborne feels like it will be extremely difficult for him to continue with the store for much longer: “I sell on Amazon, who have increased their fees this year. If I sell a new release at anything lower than RRP I make a loss - with any hardware I also make a loss. Daily transactions are now less than 10% of my 2007 figures, and takings are also less than 10% of my break-even figure. I am considering my position for after Christmas.”

Indeed, the general vibe from the people I spoke to is that for many indie stores, this Christmas may very well be their last.

Diversify or die?

Harding-Rolls agrees with the indie retailers that digital codes are not the future for bricks and mortar stores. “What is clear is that trying to build a business on pre-paid digital content and services will not replace lost sales from physical media and pre-owned games. This has forced chains to diversify heavily into merchandising and adjacent consumer electronics categories.” Accordingly, if you wander into a branch of GAME or Grainger Games these days, it’s hard not to notice the ever-expanding merchandise aisle. Indie retailers are trying the same tactic: “We are all expanding to do different things such as merchandise, toys and board games,” says Benson.

The key point is that there’s generally a lot more profit to be made on things like toys than there is on new boxed games. Hart in particular says he is trying to push merchandise to make up for dwindling profits from games, and he’s even thinking of selling pre-owned Lego. Kelvin Donaghy from 720 Games in Bodmin agrees that indie stores need to diversify to survive. “They have to evolve to whatever suits, so loads more selling of trend items like fidget spinners and POP vinyls to increase turnover.”

But not everyone thinks that merchandise and other non-game items can offer an escape route. “We’ve moved into toys, Lego, bits and pieces,” says Chris Bowman of Console Connections in Shildon. “We’ve tried different things, but without the games side of it…”

Bowman says that people tend to come to his store for one thing - games - and things like merchandise will always remain peripheral to this core, yet struggling, business. Osborne also attempted to diversify into toys in his shop, but the initiative failed, “with the result that the majority of the stock had to be sent back to wholesalers”.

The game store as a destination

“The problem facing GAME,” says Summers, “is making its stores sufficiently attractive in order for shoppers to go to the effort of visiting them. Clearly, GAME will struggle to compete on price [with online retailers], so it needs to do something that online competitors can't do - namely engage with its customers on a face-to-face level, either through good service and/or by holding events that people want to take part in.”

"Games stores still have an important role to play in educating the consumer about hardware and what products to choose"

Events are something that GAME has been building on with the advent of BELONG Gaming Arenas. The company hopes that gamers will be lured away from the internet with the promise of face-to-face competition - the website even suggests hiring arenas for birthday parties. I asked GAME how the company plans to adapt to the changing market, and a spokesperson provided the following statement:

“The high street is changing, and we’re changing with it. We are well into our journey to combine multi-channel retail, live gaming and digital services that provide gamers with the opportunity to buy, discover, socialise, compete and play, both physically and virtually. Most of our people are gamers – it’s what they do and love and this relevance to the customer is what sets us apart. We’ve opened 18 BELONG Gaming Arenas in less than a year, attracting new customers to GAME stores and providing the chance to play and test the latest tech and games across multiple platforms including PC, PS4 and Xbox One. For us, the future of retail is about serving the gaming lifestyle and that includes what’s most important to gamers, from games to clothing to live events.”

Even indie retailers are making attempts to rebrand their stores as destinations. Donaghy says: “I have just decided to move to a unit where I can offer drinks and food in a game-related lounge area to try and poach the lot who spend £3.50 on a cup of ice from Costa, and also to get some money out of the digital downloaders who still spend time in the shop chatting about games but never spend a penny in the high street on games anymore.”

But events (and drinks) aside, the analysts argue that one thing which can really differentiate high-street game stores is their ability to dispense valuable advice. “Games stores still have an important role to play in educating the consumer about hardware and what products to choose,” says Harding-Rolls, “so concentrating on hardware and devices seems a sensible defensive strategy.” Summers agrees: “For high street gaming retail to survive, companies/staff need to show a level of expertise that will make customers more inclined to pay their inevitably higher prices.”

The future

But will all of the diversifying, events and expert advice be enough to stave off the closure of high-street game stores? If we look back to the music sector, there seems to be a ray of hope. The fall in CD sales has slowed dramatically in recent years: in 2016, physical music sales dropped by just 2% in the UK, a far cry from the double-digit decline of years gone by. The indication is that everyone who wants to switch from CDs to downloads or streaming has already done so - some purchasers will always want to buy a physical product. We’ve reached a plateau.

And, perhaps counter-intuitively, the number of retailers selling CDs, DVDs and Blu-rays in the UK hit an all-time high in 2016 - in fact, the number of stores has doubled since 2009. The increase is largely due to non-specialist retailers like supermarkets and clothing stores starting to offer more entertainment products, often as impulse buys. Kim Bayley, chief executive of the Entertainment Retailers Association, had this to say on the increase: “Conventional wisdom has always suggested that the internet spelled the end for physical entertainment stores, but these numbers show that traditional retail still has a place, particularly for impulse purchases and gifts. After all, you can't gift-wrap a download or a stream.”

She also noted that independent stores had adapted to cater for “distinct tastes” by specialising in genres such as country music or world music. Could we see the same pattern emerging for independent game stores? Will there be shops that specialise in JRPGs, for example? There’s certainly been a marked rise in interest in retro gaming in recent years, and some indie retailers are considering going into old games exclusively. “I'm pinning my hopes on going backwards into retro,” says Hart.

There’s a good chance that physical game sales will reach a plateau, just like CD sales have done. At this point, everyone who wants to go digital will have already done so, leaving a hardcore group of people who remain invested in the physical product. And many people will still want to hand over physical copies of games at Christmas or for birthdays. We could also see the number of shops selling games rise - perhaps non-specialist retailers like Primark might start stacking video games at till points to provoke an impulse purchase.

Still, it looks like there’s still a very long way to go until we reach that plateau and physical sales of video games stop declining. GAME seems to have stabilized for the time being: after hitting a low of 19.25p in July, the company’s share price has rebounded to around 40p. But many indie game stores are already teetering on the brink of financial ruin. Benson reckons they don’t have long: “It's a shame but it’ll be Game Over for us sooner than you think. Game over man, game over…”

Lewis Packwood loves video games. He loves video games so much he has dedicated a lot of his life to writing about them, for publications like GamesRadar+, PC Gamer, Kotaku UK, Retro Gamer, Edge magazine, and others. He does have other interests too though, such as covering technology and film, and he still finds the time to copy-edit science journals and books. And host podcasts… Listen, Lewis is one busy freelance journalist!