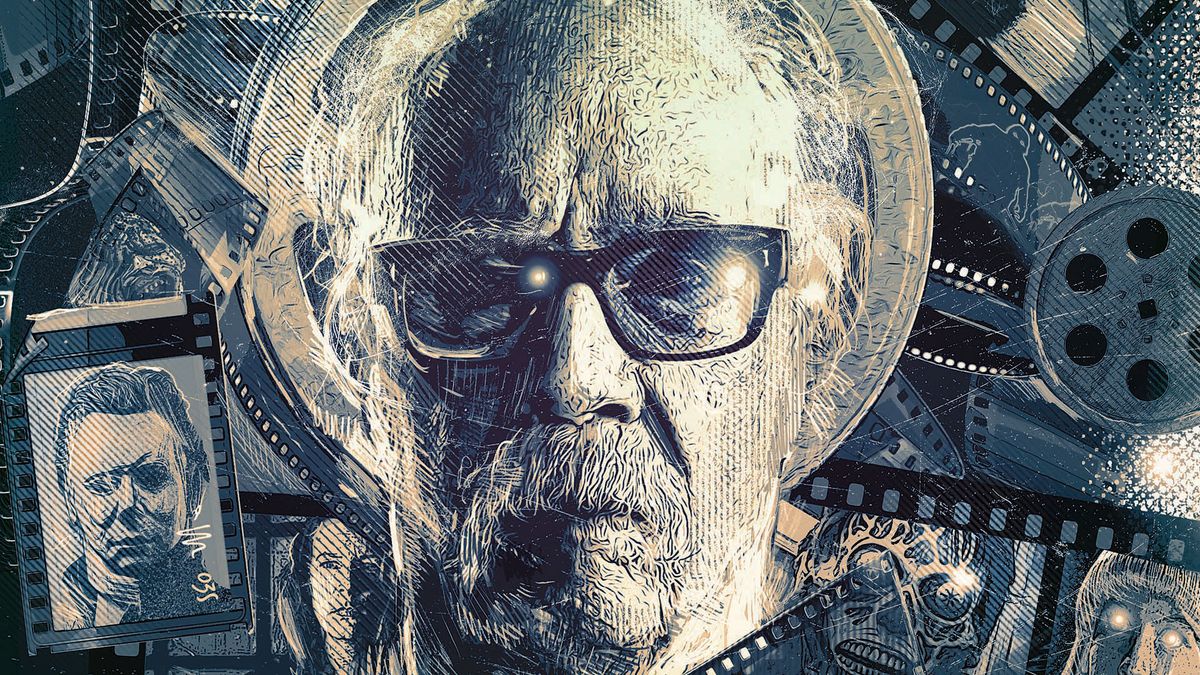

John Carpenter Interview: "I’m not the biggest fan of talking about my films – but let’s do it"

On the eve of Halloween Kills, Total Film meets the man behind Michael Myers, R.J. MacReady, and most of your favorite ’80s movies to discuss his tumultuous career, and how he’s happier than ever making music…

Our John Carpenter interview first appeared in Total Film magazine – subscribe to the magazine here for more exclusive news, reviews, and features.

Hang out on Film Twitter long enough and you’ll eventually stumble across someone posing this chin-scratcher: ‘Which director is responsible for the longest, unbroken run of classic movies?’ There are cases to be made for plenty of filmmakers: Coppola, Kurosawa, Nolan, Villeneuve; but few hold a pumpkin-encased candle to John Carpenter. Between 1976’s Assault On Precinct 13 and 1988’s They Live, Carpenter made 12 films, most of which are considered all-timers today, even if they were rarely recognised as such by contemporary audiences and critics.

Carpenter was prolific, and then some. A multi, multi, multi-hyphenate, he habitually directed, wrote, produced and composed the music for his features. He was 28 years old when he penned the screenplay for Precinct 13 in eight days, and just 30 when he changed horror forever with Halloween. He was a wunderkind to make Damien Chazelle look like a late bloomer. Today he’d be inundated with rich contracts to helm blockbuster franchise fare, or treated with the auteur reverence of a Tarantino. In 1982, after The Thing bombed, he was dumped as the director of Firestarter.

If Carpenter wasn’t sufficiently celebrated in his heyday, there’s no danger of that anymore. During an hour-long chat in late June, Total Film freely throws around words like ‘masterpiece’ and ‘magnum opus’ when describing his work – praise he accepts graciously, but not all that comfortably. Following a string of flops in the ’90s, Carpenter fell out of love with movie making. His relationship to his work is complicated to say the least. “You know, I’m not the biggest fan of talking about [my films],” Carpenter says over the phone from his home. “But let’s do it.”

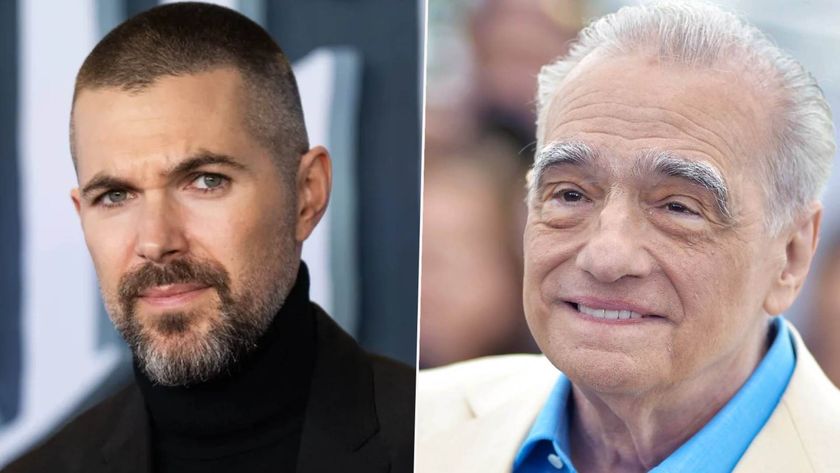

If there’s one project Carpenter is buzzed to talk about today, it’s Halloween Kills. The belated sequel to Halloween (2018) sees Carpenter return as both composer and executive producer. David Gordon Green, the new trilogy’s director, values Carpenter’s input above almost anyone else, telling TF: “It’s not like a committee of faceless studio executives giving you notes, it’s the genius that created the franchise! It makes you look good.” Carpenter, rather modestly, sees his role as EP a different way: “Everybody comments when the movie’s done. So I do the same as everyone else. It’s tedious, but that’s the way it goes.”

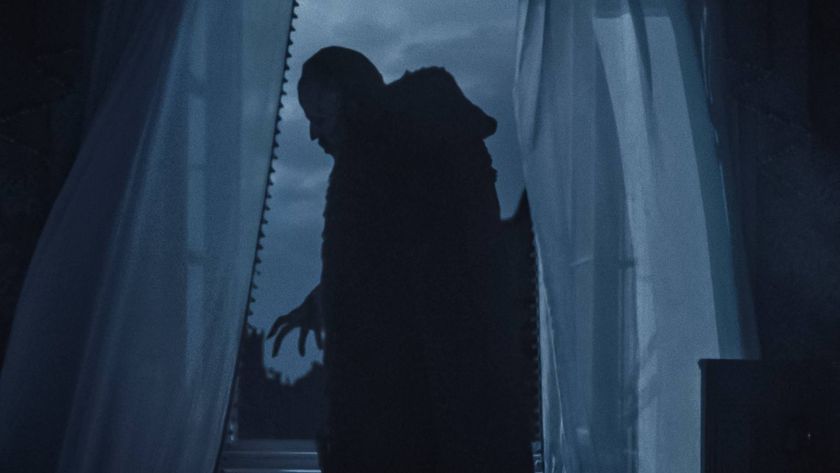

He may not be prepared to pat his own back, but Carpenter will enthusiastically heap praise on others: Green is a “spectacular director!”, and Halloween Kills “a slasher movie times 10!” It’s a film he’s thrilled to be associated with, especially because he no longer has to “suffer under the pressure of directing” and can work on the film in a capacity he still enjoys – as the maestro behind its nostalgic, menacing score, alongside his son Cody and godson Daniel Davies. “We tried some different sounds this time. We let the movie guide us,” he says. “And it’s great fun. I’m very, very proud of this score – and the movie. This is what horror films should be.”

This is what horror films should be.

John Carpenter

In a different life, Carpenter may have followed in the footsteps of his father and become a music professor himself, but a viewing of Forbidden Planet in 1956 set him down a different path. “It was mind-blowing to me,” he recalls. “Everything about it, especially because it had an electronic soundtrack. It was like I just got dosed with LSD. I thought, ‘Wow, I have to do this.’” At the USC School of Cinematic Arts he “learned how to do the plumbing” and started work on what would become his first feature film – sci-fi comedy Dark Star. Shot in pieces over four years for a grand total of $60,000, Carpenter considers Dark Star a “student film made into a feature film”, though few student films are now regarded as cult classics.

Sign up for the Total Film Newsletter

Bringing all the latest movie news, features, and reviews to your inbox

Carpenter followed up Dark Star with the Rio Bravo-inspired Assault On Precinct 13 in 1976. Other than a brouhaha with the MPAA, who took issue with the still-shocking scene in which Frank Doubleday’s Warlord guns down a young girl in cold blood while she clutches an ice cream, Carpenter remembers the film – his first shot to a schedule in just 20 days – as extraordinarily hard work: “I had no idea how tough it was going to be. But I got to use Panavision widescreen, which I loved.”

The next 12 years would prove the most fruitful, and demanding, of Carpenter’s career for a simple, but surprising reason. “Once I started [making movies], I was afraid I wasn’t going to get to do it again,” he admits. “My whole goal in life was to be a professional movie director, and make a living at it. So when a movie came along, or two movies, I’d say yes. I worked like a dog.” In 1978 Carpenter shot both Halloween and Elvis – a three-hour TV movie with dozens of locations and speaking parts. “I was so tired. But I just couldn’t say no. Especially when you’re young and starting out, you can’t say no.”

Despite the pressure to come, Carpenter remembers Halloween as the most fun he ever had directing. “That was a blast. We were just a bunch of kids making a movie. Nothing has been like it ever since. It’s always been pain!” Halloween would go on to be a phenomenon, yet it was anything but a success from where Carpenter was standing. “I thought I’d made a bomb in Halloween. Seriously, I did,” he says, doubling down. “Initially, it was a regional release. And it got a bunch of bad reviews. Some of them I took to heart: ‘Carpenter does not do well with actors.’ Ugh, my God.” It was only after the film's New York release that word of mouth picked up. “But at the time I did not know, so I was still taking jobs right and left.”

On the heels of Halloween, The Fog became one of Carpenter’s few undisputed box-office hits, but it was nearly a wreck, with Carpenter deeply unsatisfied with his first cut of the film. “I was too heavy-handed in some areas. I had fucked it up, to be honest with you. And I realised, ‘I can’t let this out this way. I have to do better.’ So we did.” As for the notoriously naff 2005 remake: “I was delighted, because I didn’t have to do anything and I got paid again – that was just wonderful!”

There’s probably a third or maybe even fourth story about Snake.

John Carpenter

Carpenter’s defining collaborator during the ’80s was a former Disney kid called Kurt Russell. The pair became “fast friends on the basis of professionalism” during the making of Elvis and would reunite on Escape From New York which, with a budget of $6m, was Carpenter’s most ambitious project at the time. Working with Ernest Borgnine and western icon Lee Van Cleef thrilled Carpenter, while Escape From LA remains his only sequel as a director. Does Snake Plissken hold a special place in his heart? “He’s a character that Kurt is passionately fond of. He convinced me to do the sequel," he says. "There’s probably a third or maybe even fourth story about Snake. I don’t know if we’ll ever make it, but I think that he deserves it.”

The Thing – or rather the reception to The Thing – would prove a turning point in Carpenter’s career. Shooting on location in Alaska, and with Rob Bottin’s demanding special effects, could have been a disaster, but Universal were “very supportive” having gone through a similar experience with Jaws – a film that turned out OK for all involved. Where the studio did have major problems was with the film’s nihilistic ending. “We actually came up with the final lines up there on location,” Carpenter recalls. “Universal, once they saw what we’d done, said, ‘Can’t you be triumphant here?’ I had a lot of pressure to change it.” Needless to say, Carpenter stuck to his guns. And what cut the deepest about The Thing’s commercial failure is that the film was exactly the movie Carpenter envisioned, no compromises. “It was hated by everybody when it came out because it was so dark. It’s the end of everything. I mean, come on!”

While it wasn’t the end of Carpenter’s career, it certainly felt that way for a while. “I was fired off of Firestarter because of The Thing. They kicked my butt to the pavement. So I was looking for a job, and I did Christine.” A year later Carpenter would be back in Hollywood’s good graces after helming Starman – a film outside his wheelhouse, but one he found mainstream success with. “It was an opportunity to do a romance. It’s amazing that it came along. Jeff was incredible to work with.”

Bridges was Oscar-nominated for his performance, and Starman’s success allowed Carpenter to get another leftfield project off the ground: Big Trouble In Little China. “I loved kung fu movies right from the first one I saw – Five Fingers Of Death. Oh my God, it was just a joy.” Shooting Big Trouble… was similarly joyous for Carpenter, but the same can’t be said for working with 20th Century Fox on the film - a fraught experience that caused Carpenter to step away from major studio moviemaking. “On Big Trouble… I was working with the head of a studio who was an intentionally cruel human being. I just didn’t want to deal with that any more.”

I loved kung fu movies right from the first one I saw

John Carpenter

Carpenter temporarily found a home at independent production company Alive Films, who offered him a simple deal: a thrifty $3m budget in return for complete creative control. Prince Of Darkness was the first project to result – a Quatermass-inspired collision of theology and theoretical physics. Darkness was swiftly followed by They Live – a “primal scream against Reaganomics” that has become increasingly relevant over the years, something that amuses Carpenter because “It has a big fight in the middle that has nothing to do with anything!” Imagery from They Live has been utilised in anti-capitalist protest art, but in recent years Carpenter has found himself stamping out incorrect readings of his work. “The right wing is trying to adopt that movie for its own. They think that the aliens are Jewish. For fuck’s sake – come on, you idiots!”

In retrospect They Live was the end of an era. It would take four years for his next film – Memoirs Of An Invisible Man – to reach screens, and the films that followed largely failed to capture the creative spirit of his ’80s heyday. He eventually burned out following 2001’s Ghosts Of Mars (“I don’t like getting up in the morning. I’d rather sleep in.”), and wouldn’t direct a feature film again until 2010’s The Ward. What was it that tempted him back? “The pressure. Just pressure,” he admits. “And I got to work with some really talented young ladies.”

Things changed drastically for Carpenter in 2015, after he survived a “pretty serious illness”. In the years since he’s focused on the things that make him happy: namely videogames (he's currently whiling away the hours with Assassin's Creed: Valhalla and Fallout '76) and music. Earlier this year, he put out his fourth studio album, Lost Themes III, and in addition to his work on the new Halloween trilogy, Carpenter says he’s agreed to score another movie later this year. He doesn’t rule out a return behind the camera either. “I’m working on it. I’m always thinking about it. I’m always looking out for a project that would be great. I would do it, sure, but the conditions have to be right. There has to be enough money, and there has to be enough time.” He even has an idea, and he’s only half-joking: “Kurt’s Santa Claus now – I want to try to get him to play an evil Santa Claus! I think he’d be great.”

As for Halloween, with the final film in David Gordon Green’s trilogy due out in 2022, Carpenter could be about to leave Haddonfield behind for good. But, ever the realist, he doesn’t see this as the end of the road for Michael Myers. “I’d like to caution you that if Halloween Kills and Halloween Ends make money, I don’t know that you really have seen the end [laughs]. Maybe of my involvement! Maybe they will say, ‘We want a fresh approach. Let’s get this bum out of here!’ Whatever… See, I’ve changed my whole feel later in life. I embrace everything. Everything is wonderful.”

Halloween Kills reaches UK and US cinemas October 15. For more, check out the Halloween Kills issue of Total Film.

I'm the Deputy Editor at Total Film magazine, overseeing the features section of every issue where you can read exclusive, in-depth interviews and see first-look images from the biggest films. I was previously the News Editor at sci-fi, fantasy and horror movie bible SFX. You'll find my name on news, reviews, and features covering every type of movie, from the latest French arthouse release to the biggest Hollywood blockbuster. My work has also featured in Official PlayStation Magazine and Edge.

Most Popular