Keeping it real: Meet the developers leading the fight for live action in video games

OPM discovers why live action continues to be alluring to the video game industry

Lights, camera... gameplay? Erica is a feature-length thriller following its titular character as she becomes embroiled in a conspiracy stretching back to her father's mysterious death during her childhood. It features talented actors and excellent cinematography. But she never makes a decision without you having some input.

Erica's creator, Flavourworks, is a game developer, not a movie studio, tucked away in a cosy games hub in London. Following Jack Attridge, the studio's co-founder and creative director, around the labyrinthine building full of props from the set, it's impossible not to keep an eye out for juicy development secrets. Then we sit down to chat.

"When we're just walking around the building now, we're not thinking about traversal. We're not getting stuck on a corner of a plant pot," Attridge says. He's right. "We knew that doing film, we'd lose something, which was that ability to walk around the environment, to traverse," he continues.

"When we start making a game it's usually about exploring 3D space. Unity being a popular game engine that people use, you can put the 3D cubes down, then you're like, 'how do I move this around the environment?' And it means that all of your ideas come from conflicts in traversal, or how your relationship with that environment changes as you're moving something around."

Moving pictures

While Attridge acknowledges the influence of FMV games of old, he doesn't like to think of Erica within those confines. The main thing that interests the studio is making games strictly based around narratives, in the same vein as the likes of Until Dawn or Detroit: Become Human.

"We felt that before we'd even said 'We're definitely going to do live action,' the thought was, 'If we weren't doing live action, would we design this game the same way as we are now?' As in, would we not have traversal?" says Attridge. "And the answer was, 'Yeah, we would do it the same way, because traversal is not where the storytelling happens.' [Something like] actually navigating down and up some stairs for us isn't where the stories are."

The format has to play to the strengths of the game you want to design. "The thing that games do really effectively, you can have a character jump through a window and an explosion with lots of smashed glass, and that's pretty affordable in a game, but that's the thing that's really expensive in a film," says Attridge. "And the thing that's really expensive in the game is trying to render something close to a human face and an emotion. That's the thing that's affordable in film."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

If you haven't yet played Erica, it resembles a movie, but it's far from being one. Controlled with swipes from your connected phone or on the DualShock 4 touchpad, scenes seamlessly blend together as you make quickfire decisions or make Erica interact with the world, for example by unwrapping a package or wiping a mirror clean.

"We want to just make sure you never feel like you are lacking control. The other rule we had along with the [ability to always remain] silent was you have to interact every 15 to 20 seconds," says Attridge. "If I ever get tricked into leaning back and putting this down and I have a sip of this, and then a choice comes up? Game over."

As a player you barely notice how detailed the decisions are, or even that you can remain stoic throughout (aside from in the game's mirror-based introduction). But that speaks to how well Flavourworks pulled things off.

"It was very important to us that the story was told through the player being involved and not taking turns with the storytellers." Attridge has a background in film, but it wasn't cinema that gave him the inspiration to do a live-action game: "One of the seeds that made me really inspired to start FlavourWorks was going to an immersive theatre show by PunchDrunk called The Drowned Man."

Unlike traditional theatre, where you sit in a seat and watch the stage, immersive theatre has the audience wandering a space where things are happening all around them. "[They got] 200,000 square feet of building over four floors, and completely built every inch of that building to be a world," he says, "You're enveloped in this ambient moody sound, and music, smell, and you feel temperature, and you can taste and touch anything. And you can flick through any prop or object in this world. It's all detail you can play with, right? There's like no limits. And so I saw that and thought 'why am I even making video games?'"

Attridge wanted to take that energy and translate it into gaming. "There was no wrong way to do [the play], right? Like you went in with your curiosity and that was it. It wasn't about game overs, it wasn't about skill," says Attridge. "With Erica the idea was 'If I walk into a room early, do I see a hero or whereas if I walked into there late I saw a villain, based on what I saw?' And so that's the idea of Erica, that everything comes to the end, and based on what you've seen, it'll colour your expectations of what you think is going on."

Search party

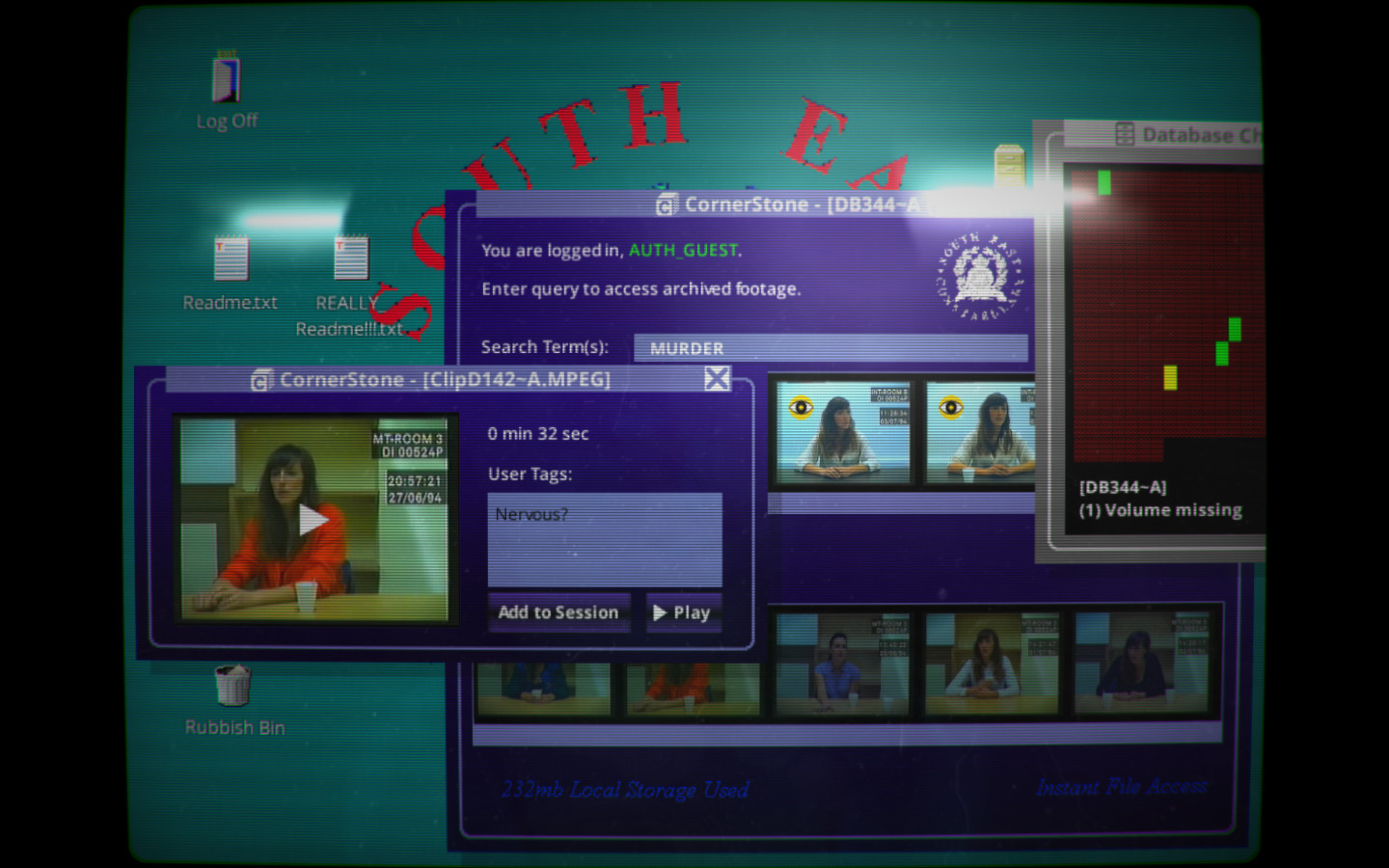

Watching an interactive movie might be simple enough, but another take on the live-action game gets you Googling. Telling Lies is Sam Barlow's second game in the genre (Her Story came to PC in 2015), and has just launched on PS4, though his journey before going indie included the likes of Silent Hill and Legacy Of Kain.

Unlike Erica, which has a similar runtime to your average film, Telling Lies gives you a database with hours of recorded videos (from spy cameras to single halves of video calls) and asks you to try to piece together what exactly went wrong on an FBI Agent's undercover mission. The database can only list five videos at a time, though, taking you to the point in the video where the word you searched for appears. Like Flavourworks did with Erica, Barlow found the live-action nature of images and the non- traditional gameplay made Telling Lies approachable to just about anyone, no matter their gaming experience.

"It's like Googling. You know how to Google. You get to just explore these clips, like they've seen [on] TV shows where a cop is sat in front of a computer searching through a database to find that little clue that will save the case," says Barlow, "whereas, you know, like a game like Uncharted is incredibly cinematic, but your job in that game is to be a stuntman, right?"

"You have to be the person that runs the character through the exploding street, jumps at the right time, lands in the right place, turns and shoots the guy in the head. Like that is a lot of pressure. That combination of genre, the look of it, the context of what you're doing, is all very welcoming to people who are not necessarily gamers or are lapsed gamers. That's a really cool thing."

This feature originally appeared in Official PlayStation Magazine. Subscribe now to have every new issue delivered to your door.

"I think the reason I ended up with live action was because I was thinking about character performances, and emotions, and storytelling. And that led me to, 'Oh, if I do this with live action, it's going to feel more authentic,'" says Barlow. "But I'm already thinking of this game framework where it's not important to have a frame-by-frame response. And I'm in a world where I'm not trying to create this systemic explorable world."

But that didn't mean he wanted to make something linear. In a sense, Barlow still thinks of his games as being open world. "I make the comparison to Metroid in that what is cool about a Metroid game is you're exploring this world, and the backtracking where you revisit rooms is about building a mental map of the space," he says. "Similarly, with [Telling Lies], as you learn things about these characters, as you learn simple things like character names and stuff, that gives you access to parts of the story. When you rewatch things from a different perspective, now you have gained insight and knowledge of what's actually happening."

These clues can lead you to make further discoveries by searching the database, and as you play it genuinely feels like you're uncovering what happened yourself. "You're watching the story, but you're also thinking and planning what you're going to type next and putting the pieces together. There was a neat thing where the gameplay and the story were kind of the same thing," says Barlow.

"Like if I'm thinking 'What does this character really mean? And who is this person she's talking about? Oh, how did they first meet?' That is both a story thing and it's a gameplay thing, and there's enough frequency of me typing stuff and thinking things and clicking things that actually, just on a physical level, I'm still engaged in this game, it's not really about sitting back and watching."

Using live-action actors helps to sell the idea that you're really peeking into other peoples' lives, but to Barlow the way the game plays make it the opposite of a film. "I remember pitching it to Logan [Marshall-Green, who stars], and I think he loved this as an anti-movie, right?" he says. "These conversations are longer and more sprawling and have moments of silence and have people not speaking and have this texture to them that is not what you could get away with in a movie."

"My big sticking point was, as someone that was really interested in telling character-driven stories, the more I'd worked with actors, the more it felt like – this isn't obviously rocket science – but like trying to tell a story about characters having the character performance in there is a big part," he says.

And to avoid his budget skyrocketing on complex animation, it made sense to do it on film. "[For my first project] one of the things I said: was, 'I will get rid of the 3D exploration. I'll come up with a game idea where I'm not reliant on being present in a 3D space and how immersive that is, but what happens if I get rid of that?' And then the other thing I was frustrated with was, so I wanted to make a game with no systems, nothing systemic in it."

Between the lines

Barlow might owe his conversation-searching style to real-life tragedy. "When I very first had the idea, I thought 'Oh shit, I'm gonna have to create the most complicated flowchart to figure out how this game works.' But then I found a series of police interview transcriptions, [from] this real-life case online in text format," says Barlow.

"So I grabbed these, and I stuck them in the game. Or in a very crude version of the game that I think I made in like Excel with Excel macros. And I played this real-life transcript of the series of interviews with this kid who was accused of murdering his parents. And it was super-interesting because it actually played okay."

Playing through his hastily created morbid database to test if the idea for the gameplay could work resulted in a success. "I knew nothing about this case," he admits. "I just dumped this stuff into my prototype. I noticed that this kid kept talking about money, right? They would ask him questions about 'What are you doing this summer?' And he'd be like, 'Oh, me and my girlfriend were gonna go on a trip but I haven't got enough money.' 'What are you doing tomorrow?' And he's like, 'Oh, I need to go to the bank'. And like, there was this subtext that kept coming up. And you know, I would then search for words to do with money: cash, bank, money, loan, whatever. And it became clear this was like a subtext throughout the whole thing."

"And then I go and look online and it turns out this kid murdered his parents to get the inheritance. So like, it wasn't a huge mystery, but I was like, 'Oh, it was really neat that I discovered this subtext through this word search mechanic,' [...] and there was something exciting about leaping back and forth through these different answers he'd given."

"Using different mediums inside the game makes the whole world of the game feel richer."

Mikko Riikonen

Barlow and his team are gearing up for a new project, and it sounds like it will continue what has now become his style of live-action gameplay. "It's hard to not do it. It feels like... it's not a cheat, but there are some aspects to it that are so great compared to how I used to have to work where I get to spend a lot of time thinking about the story and the characters and how that works. When we shoot this thing, you get to work with actors in a way," says Barlow.

"There's just something really neat about being in the space of moving things around and figuring things out with the actors. And yeah, that ability to reach people that are not traditional gamers is really neat."

On the other hand, D'Avekki Studios' games don't get more traditional. The team – headed up by husband/wife duo Tim and Lynda Cowles – originally got their start making tabletop murder mystery games.

"Designing physical games has definitely helped shape our video games. Our physical Murder Mystery Flexi Party games already contained branching dialogue and random murderers, so it was easy for us to implement that in our FMV games," Tim Cowles tells us. "There's definitely two core factors that power our design philosophy in both: is it fun? Is it interesting?"

D'Avekki's games are more traditional FMV where you do things like solve mysteries or supernatural events, though its more recent work incorporates point-and-click elements as well as dialogue branching. The live-action actors help with creating that player connection to the plots and characters.

"When those characters address you directly it becomes even more immersive," says Cowles. "The quickest and easiest thing to do with live action is animate a character! Walking, running, punching, picking up things, talking and so on," he says. "While it can still be quite expensive depending on the location, the environment itself is potentially far easier and quicker to set dress than to rebuild using 3D tools."

Live action has to serve a purpose, and naturally it can't be used for every genre of game. "I think the games we've released so far are largely character- driven, and involve you having many intimate conversations with people, and that just works amazingly well as FMV," says Cowles. "They're not as complex as traditional point-and-click adventure games, and they definitely don't require fast reflexes or controller wizardry, so that does make them more approachable. They're also great to play with friends in a couch co-op mode."

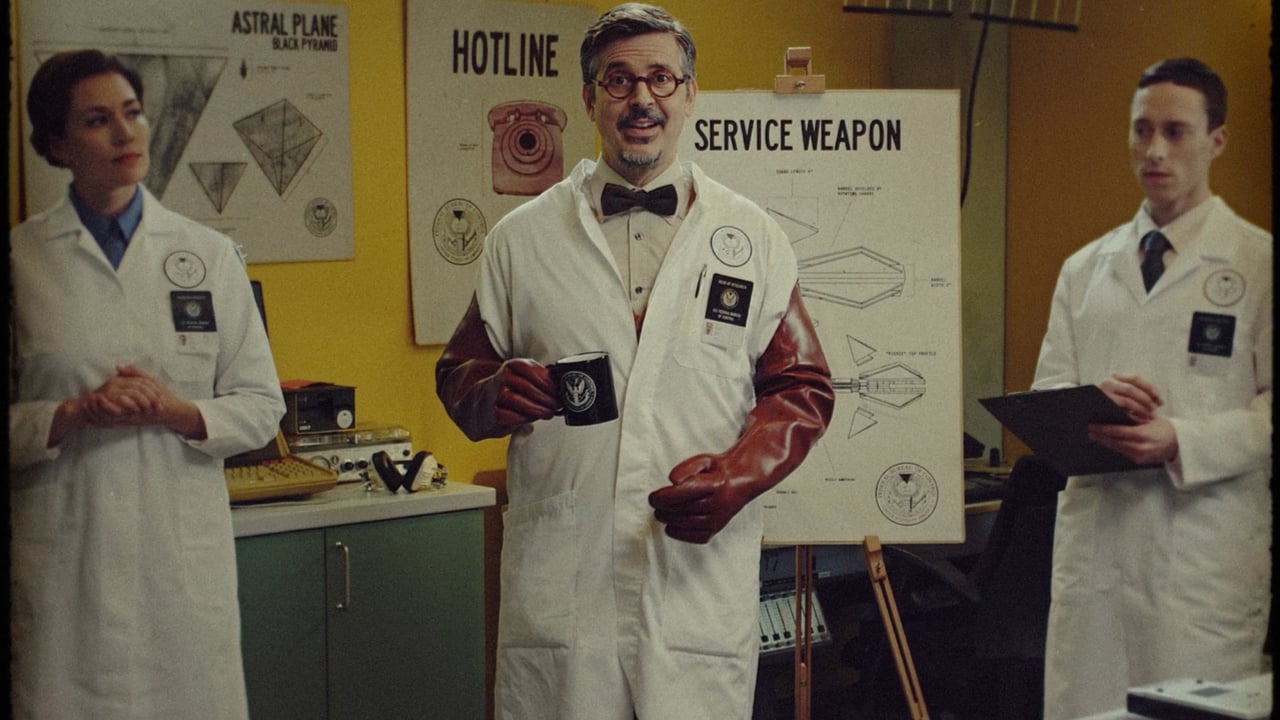

But what if you could use live-action to make a game with massive amounts of fast-paced action? The first thing that jumps to mind is Max Payne's smug, smirking mug, his (at the time) photorealistic face bearing the likeness of Remedy Entertainment's co-founder, writer, and creative director Sam Lake. Over the years, Remedy has been devoted to incorporating live-action video as part of its games The culmination of this is Control, where some live-action cutscenes add to the game's otherworldly tone, and superimposing live-action shots on CGI ones creates an eerie quality.

"We've always had an open-minded approach to different ways of telling stories. So it's not about using live action just for the sake of it, but because we want a compelling experience using the best techniques available," explains Mikael Kasurinen, the game's director. "With Control, a huge part of the tone comes from an unconventional combination of elements. You see the mundane clash with the strange, secrets and truth breaking apart, and things rolling forward in a way that you don't expect."

My dear darling

In Control, Jesse Faden explores a shifting supernatural building that's the headquarters of the Federal Bureau Of Control. Taking over from its previous director, Trench, she is guided at times by his echo, and an unexplained psychic being, Polaris.

"With the Trench presences, we were looking at double-exposure photography quite a lot and researching on how we could bring that sort of feel to the game with live-action," says Mikko Riikonen, the game's principal cinematographer. "For the Polaris blended videos, there were different video art and live-action effect shots researched and tested before we found the ones that were used in the final version."

"Having them as live-action would add a layer to the game that would be very hard to achieve with using only 3D. And I think using different mediums inside the game makes the whole world of the game feel richer, and in some weird way a bit more real," says Riikonen.

You follow in the footsteps of Dr Darling, who forever seems just out of reach, and is the only character portrayed solely through live-action videotapes. Thanks to modern technology, live-action film in video games has far outgrown its FMV roots, and there's no set way you can expect to see it used.

It can gamify a cinematic experience; have you search through a voyeuristic database; create a murder mystery with plenty of credible suspects and witnesses; or add extra flair to a Triple-A action game. Just like the films and television live action is so closely associated with, there's great breadth in the ways live action can be used in games, and it provides real creative advantages for developers. What will we see them using it for next? We'll have to hit Play, and watch for ourselves...

Looking for the latest information on the PS5 and PS4? Then you'll want to subscribe to Official PlayStation Magazine to get it delivered straight to your doorstep, and check out Magazines Direct for all of the latest offers.

We are Play magazine, the biggest-selling,100% independent, magazine for PlayStation gamers. Founded in 2021, it's brought to you by the same team of writers, editors, and designers as the Official PlayStation Magazine, with the same deep industry access, quality of writing, and passion for all things PlayStation. Follow us for all things PS5, PS4, and PlayStation VR.