The original designer tells us how the Uncharted series evolved, and how he evolved with it...

This interview was conducted by Official PlayStation Magazine prior to the release of Uncharted 4: A Thief's End

Richard Lemarchand knows a thing or two about laying the groundwork for great games. Now an associate professor teaching game design at the University of Southern California, he’s a Crystal Dynamics and Naughty Dog veteran who’s worked on the likes of The Legacy Of Kain: Soul Reaver and the original Uncharted trilogy.

The lead game designer on the first Uncharted (and co-lead game designer on both Uncharted 2 and 3) tells OPM how PlayStation’s biggest franchise evolved, and how he evolved along with it...

OPM: What was it like at Naughty Dog in 2005, when you were about to start working on PS3?

Richard Lemarchand: It was a very exciting time at Naughty Dog. I remember it quite vividly, though bits are blurry because it was very busy. I’d joined the studio in mid-2004 to help finish up Jak 3. In working on that, I kind of got my feet under the table. I was fortunate enough to sit in on many of the early design meetings for a project which had the codename of “Big” – this would become Uncharted.

[Then with Jak X,] we were making a fun game that was highly playtestable. It was Naughty Dog’s first online multiplayer game, and so the studio had a sense of breaking new ground even as we were wrapping up work on PlayStation 2. I think it’s good to be in a creative position where you feel you have some kind of mastery of an area, but you’re also pushing ahead into new territory. That was writ large across the creation of Project Big.

There were regular meetings of this core creative team developing a new engine specifically for PlayStation 3. That included Evan Wells, Amy Hennig and Bruce Straley. Amy and Bruce, of course, went on to creative direct and game direct on Uncharted 2.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

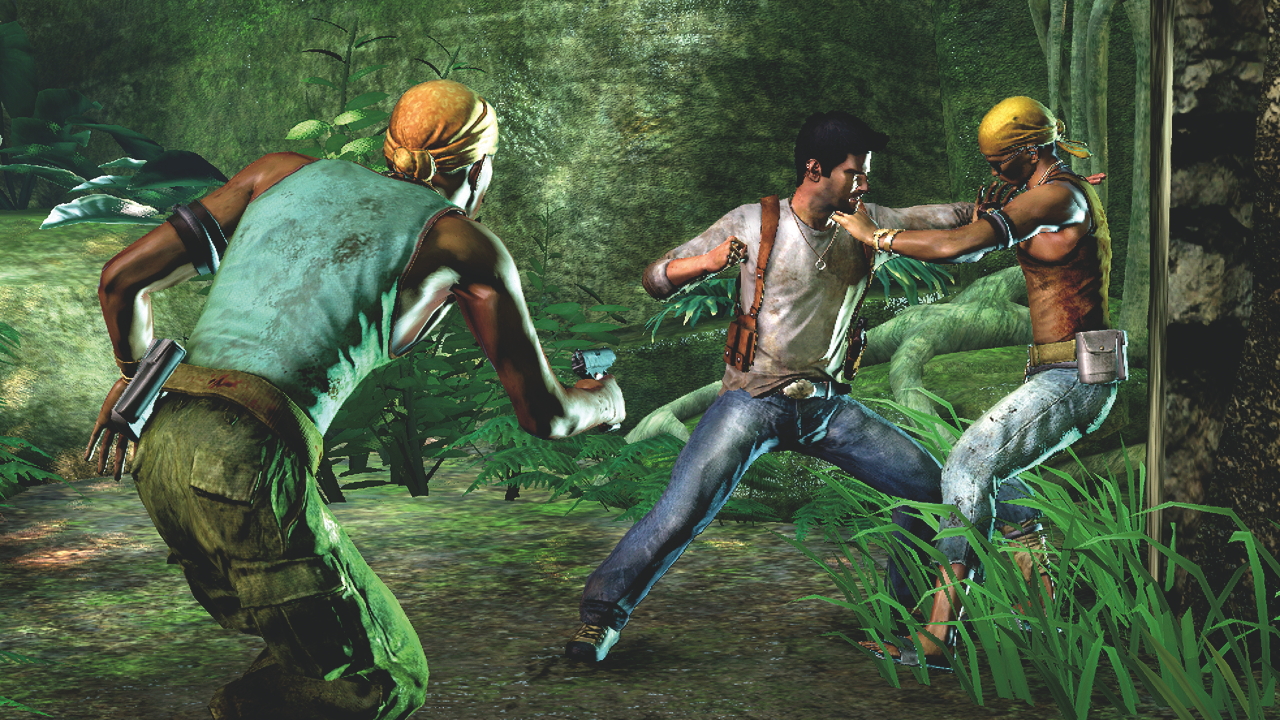

And the course of the creative development of the project had a few twists and turns. The game became about a protagonist who was older, in their late twenties or early thirties, that used a lot of the same verbs as Jak – running and jumping and shooting and brawling. But it also became about evolving those mechanics to take advantage of the increased power of PlayStation 3 and push its boundaries, in terms of the sophistication of run-and-jump shooting mechanics in character action games.

OPM: How did Uncharted stretch those limits?

RL: For a long time, Uncharted was set in an entirely different genre [early plans involved a post-apocalyptic, underwater game called Zero Point]. But by the end of 2005, we’d hit upon the idea that it would be a reinvention of the classic action-adventure genre. That was a time I was lucky to see Amy Hennig doing one of the things that she does so incredibly well: deep research into games, movies, literary fiction and TV. She went mining for the resources that would become the heart of Uncharted.

By resources, what I mean is lists of things – lists of nouns and verbs. Amy would watch a film like the classic [’30s] adventure King Solomon’s Mines and write down everything that she saw the protagonists and antagonists do. When someone ran along the corridor and the ceiling was caving in behind them; when someone had a fight with a friend which made the friend become an enemy – Amy would write down all of these things. She’d kind of decompose action-adventure cinema in a way that we could then sift through the elements and reconstruct a new kind of cinematic action-adventure game.

OPM: At what point would you say you got a sense of Project Big being something truly, well, BIG?

RL: As soon as I went for an interview [at Naughty Dog] – in fact, even before I went to interview – I knew something special was happening. I knew it was a studio that liked to work hard but worked smart, and that it constantly strove to find a good balance in its creative practices and in the content and quality of its games.

I do think that’s something very important and kind of under- discussed in game development circles. Game development is a hugely rational activity where we bring all of our cool analytical skills to bear on what we do, but it’s also a creative, ‘right-brain’ activity, trying to pull new ideas out of the air from who knows where.

It’s also important for a development team to be able to, in a sense, keep the faith throughout the course of development. Often, the difference between an excellent game and a game that crashes and burns can be the belief the developers have in it.

Richard Lemarchand - The major games, from Kain to Drake:

1999 - Legacy of Kain: Soul Reaver

A PS1 action-adventure classic directed by future Naughty Dog colleague Amy Hennig, Soul Reaver lets you switch between material and spectral planes. It sets a template for cinematic action and compelling characters, while looking astoundingly pretty.

2004 - Jak 3

Lemarchand switches Crystal Dynamics for Naughty Dog and starts by working on the final entry of the Jak trilogy, a showcase for the studio’s ability to push PS2 to its limits.

2011 - Uncharted 3

Working with Jacob Minkoff as co-lead game designer, Richard delivers the final PS3 instalment of Drake’s adventures. The debate rages over which entry is the best, but everyone agrees the desert section is simply stunning.

OPM: Is that a cultural thing, or is it more related to the technical side of a game?

RL: I think it is largely cultural. But it’s a sort of alchemic ‘as above, so below’ situation, right? Because culture is situated in our thoughts and actions – our perceptions, thoughts and actions as individuals. Yeah, there’s lots of great writing to be done around the specific kinds of creative culture pertaining to game development.

But I think that having faith in yourself and those around you is very important. Being prepared to listen to them and hear out their ideas in-depth, and then – when necessary – being able to take them to task and argue through something difficult and complicated in a way that fosters respect and doesn’t become destructive. The tension between those things is a complicated line to walk, but a hallmark of all of the best creative endeavours I’ve ever been a part of, I would say.

OPM: Having worked across the first three Uncharted titles, how do you feel you have evolved as a developer?

RL: Oh, I changed hugely across the creation of the first three Uncharted games. I’d had a big shake-up in my personal life round about the time the first game was going into development. I think that when you go through something difficult in your personal life, it can be harmful and damaging – but it can leave you primed and ready to be open to new experiences.

I learned a huge amount from the people around me. A vast amount of what I now teach in the USC games programme came out of the roughly seven-year period that I spent working on the Uncharted games. Finding new ways to structure my thinking about game flow and level flow, working at a more macroscopic level at first, and my ideas about story development – Amy Hennig was already hugely influential on those. This focus on the verbs of the game mechanics and the nouns; the things that appear in the game; the kind of interactive mix that that creates; and how that can work towards – or in tension with – traditional kinds of storytelling techniques.

In the course of creating the Uncharted games, I became more familiar with Robert McKee’s book Story. The techniques that he describes about how organising the motivations and reactions of the characters throughout the course of a story had a big impact on the way that the Uncharted games were constructed. There was an overall shift in focus in my thinking from stories as plot, towards stories as the evolution of character. I think that’s the big shift underlying the renaissance in videogames as an art form, a literary form, a cultural form we’re seeing at the moment. Plot can be interesting, but character is the stuff that we understand, because it’s the basis of some of the richest and most important parts in many of our day-to-day lives.

OPM: Story maturity in the Uncharted series is key to its success, as are those set-pieces, of course. Was it a conscious decision to make a game that was enjoyable for both players and observers?

RL: We had an awareness that that might be the case – or we hoped it would be the case – but I don’t think we were prepared for how much we heard about it once the game had shipped. Now the tutorial aspect of games is very much to the fore, whether it’s a family or a group of friends watching a single-player game, or eSports and Twitch.

OPM: Looking back, do you have any particular highlights of working on the series?

RL: I’m still proud of the peaceful [Tibetan] village section in Uncharted 2. It connects deeply to some of my long- standing philosophical thinking about game development. Certainly Tale Of Tales, and their concept of the “not-game,” which was in higher currency at the time, gave me the confidence to take that section of gameplay and run with it.

I was responsible for co-designing and producing it. I ran around teasing bits of work out of everyone who would give me some of their time. I had a sense that experiential gameplay – gameplay that is not as driven by the traditionally game-like systems of resources and goals, but by the interactive and narrative experience – that style of gameplay had to be quite rich. Quite dense with animation and graphics, sound design, dialogue... and so it took a push from me at a point in development that was already very busy trying to take the game to Alpha. But it was very rewarding. I was happy to see the warm critical reception that that part of the game got.

I think part of that warm critical reception was that it came at a point in the game that the dramatic tension had really been dialled up to 11 and had been held there for a long time. The game used that space of relief well to kind of reset the emotional timbre, and to allow us to build again towards the final acts. It’s significant that Bruce [Straley] and Neil [Druckmann] were some of the generators of that particular idea, and I do think that they used those techniques to incredible effect in The Last Of Us.

I’m very happy at the rise of wonderful experiential games like Dear Esther and Everybody’s Gone To The Rapture, and all the other indie games and art games that we’re now seeing and are pushing forward the frontiers.

OPM: How do you feel about Uncharted 4, having not worked on it? How excited are you?

RL: Well, of course, I have a pang that there’s an Uncharted game coming out that I didn’t work on! Though that has been the case before. There was the PS Vita game [Golden Abyss], and there’ve been a number of other awesome creative endeavours around Uncharted.

But that pang of maybe some kind of fear of missing out in a game developer sense is well overridden by my excitement to play the game. It’s going to be the first Uncharted game that I can play from a cold start as a huge fan of Naughty Dog’s entire oeuvre, so I really can’t wait to get in there. I hear wonderful things from my friends at the studio. I think it’s going to be huge.

This article originally appeared in Official PlayStation Magazine. For more great PlayStation coverage, you can subscribe here.