How Warioware nailed the minigame formula for generations to come

Nintendo’s reign over the handheld market has never faced a stronger threat than the bite-sized mobile titles on your phone or tablet. They’re cheap, cheerful and immediately accessible. WarioWare, Inc: Minigame Mania! however, beat them all to the punch.

In 2003 the idea of a game split into hundreds of smaller ones, each roughly five seconds long, seemed, well, demented. How could you even learn the controls if, after a single bite, the next plate was thrust under your nose like some slapdash taster course? How could you derive satisfaction from such meagre investment? The design turned out to be not only fruitful – kickstarting an irreverent new franchise for Nintendo that later saw releases on GameCube, DS, DSi and Wii (and soon Wii U with the upcoming Game & Wario: see page 51 for a preview) – but also prescient, predating the ethos that now powers the mobile market. That ethos? Gloriously instant gratification.

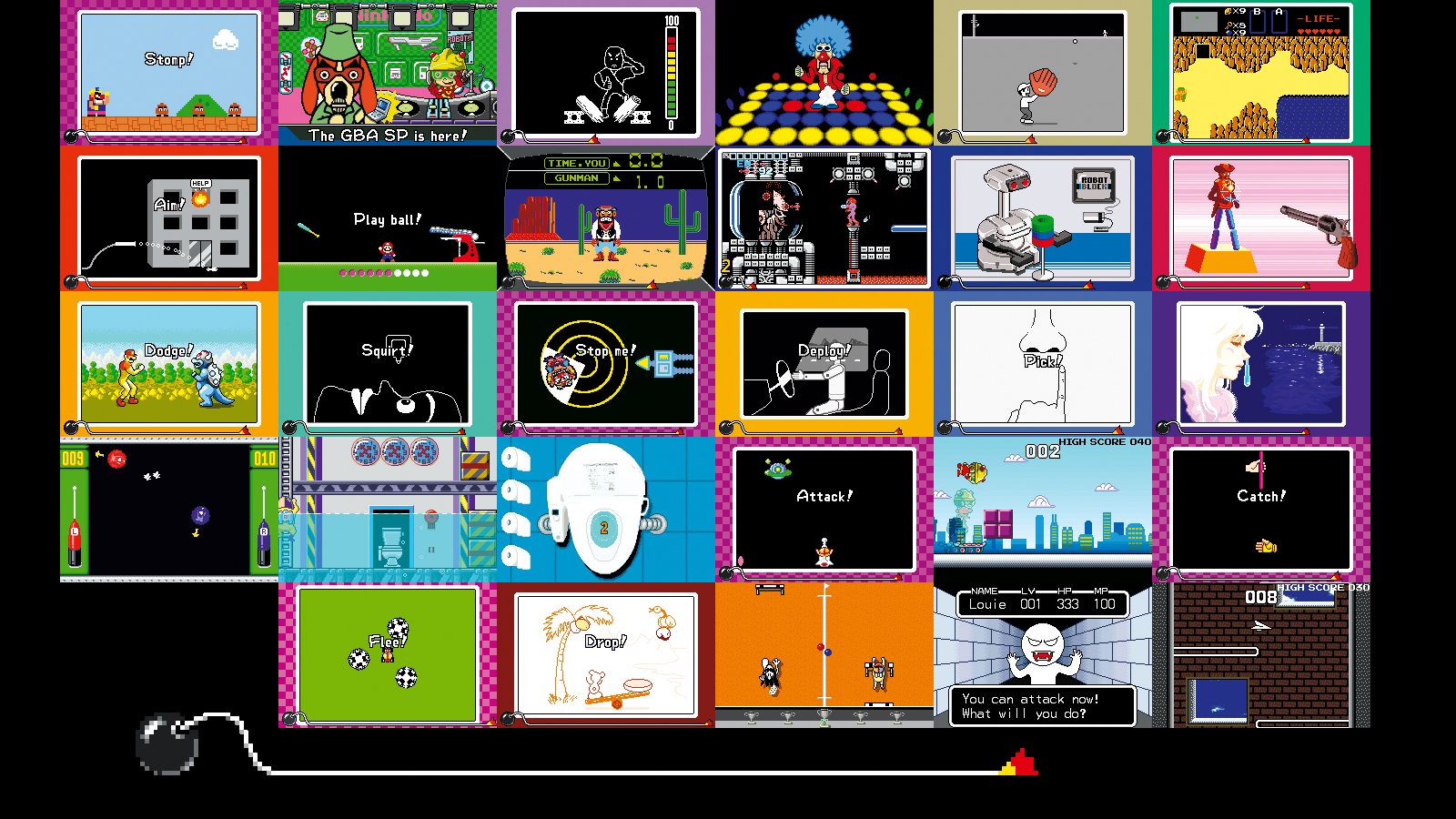

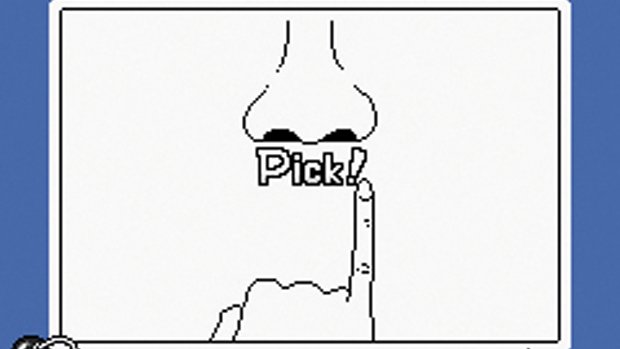

The rules were simple. Levels contained ‘microgames’ (presumably smaller than mini-games, but bigger than nano-games), which players tackled at random. You might launch a rocket, jump a shark, score a basket, brush some teeth, pick a nose or use a brolly to shelter a kitten. The catch was that you only had four lives. Let your kitty get wet, for example, and you lost one. The longer you survived, the faster the speed got. Survive a barrage of 20 or so and you advanced to the next level.

Halfway through levels lay boss fights, chances to restore a single lost life. These were slightly longer: you might fight a NES-style Punch-Out!! bout, or fly a spaceship in a top-down shooter, or bat balls from a tricksy auto-pitcher. True to WarioWare, these small, but perfectly formed gameplay nuggets stuck around just long enough to offer a challenge, but never outstayed their welcome. Of course, any videogame lives and dies by how it plays, and thanks to WarioWare’s sheer variety, there were a hundred ways in which it could fail.

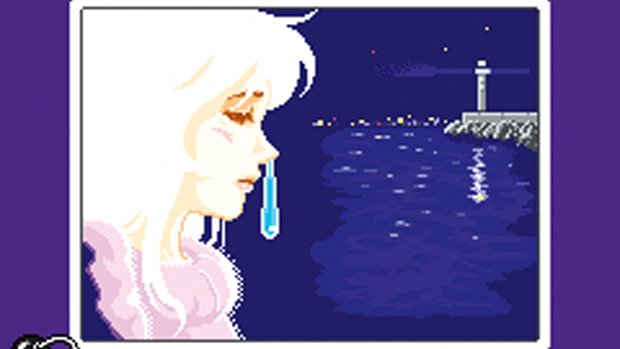

Aside from a few duds (catching a falling pole, or hammering A to eat bananas were about as riveting as they sound), there were no glaring weak links. This is down to a host of different characters packing 25 microgames a piece. The hyper-intelligent alien, Orbulon, offered Mensa-lite games that rewarded mental agility, rather than reaction times: remembering a dance sequence, say, or quickly completing a sentence (“This game is a) Stupid, b) Great or c) Ridiculous.”). Mona, meanwhile, geared hers around human physicality: threading a needle, perhaps, or using some eye-drops.

Nintendo fanboy 9-Volt’s set was arguably best, taking you on a whistle-stop tour of retro franchises: you blasted Duck Hunt fowl, dodged F-Zero racers, leapt Donkey Kong’s barrels, killed Metroid’s Mother Brain and, in an even more nostalgic nod to pre-Mazza Nintendo, hoovered a mess with the Chiritorie vacuum cleaner and grabbed plastic balls with the Ultra Hand. Impressively, these microgames weren’t just recreations, but were actual slices lifted from the games to which they paid homage.

"WarioWare demonstrated another side to Nintendo, sometimes sophisticated, but also content to roll around in the infantile muck."

Not every character made sense. Dog and cat cabbie duo, Dribble and Spitz themed their games on sci-fi and ninjas, while, erm, ninjas, Kat and Ana, based theirs on nature. Hmm. Elsewhere was Jimmy T, a disco enthusiast with a penchant for groove, so, obviously, his games revolved around, er, sports. In its scattershot way, WarioWare demonstrated another side to Nintendo, sometimes sophisticated, but also content to roll around in the infantile muck (Dr. Crygor’s level takes place over a toilet). Both sides of this split personality informed the story.

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Yes, there was a story. One evening, as Wario chills on the couch watching TV, a news report explains how game sales are exploding. So he joins the dots: make games, make money. That’s what the guy’s all about, after all. Developers aren’t known for their bulging wallets, however, so Wario enlists the help of people, pets and aliens to form WarioWare Inc.

That’s as far as the story went, but if you took it to its logical conclusion and introduced a bit of philosophy (stick with us), it made a weird kind of sense. In a way, players adopted the mantle of videogame tester, trial-running each developer’s scattershot demos without the inconvenience of having to type up a bug report afterwards. Or you might say players were unwary focus group sit-ins during some mad brainstorming session, each microgame a sales pitch for a prospective full-fat title. Whatever theory you favour, WarioWare was a lot cleverer than it seemed.

It was a lot longer, too. Five seconds of gameplay isn’t much, but multiplied by eight characters, each with 25 microgames, you have... well, we were never any good at maths. But we do know each one could be attempted in isolation from the rest and this offered a whole new spin. Rather than spend time frantically working out what to do (a one-word instruction like ‘throw’, ‘bounce’ or ‘pick’ was all the assistance given), you knew what to expect and could therefore chase your own leaderboard records. Microgames didn’t just get faster over time, either. Catching a piece of toast was even harder when a few bites had been taken from it; fleeing giant footballs demands skill when two become four. Master these and there was more fun to be had. After conquering a set of each character’s microgames, you’d unlock a longer mini-game to play at any time. Longer experiences, such as Skating Board and Paper Plane, veered even closer to mobile titles of today, the endless runners in the vein of Jetpack Joyride and Canabalt.

So, while WarioWare, Inc: Minigame Mania was indeed a precursor to the undemanding insta-fun downloadables occupying iOS and Android, it was also, in a funny way, a fitting tribute to where it all started: Game & Watch. Like WarioWare, Nintendo’s 1980s LCD portable offered not just one game, but several – 59 games across 59 dedicated models. Titles such as Fire, Balloon Fight and Vermin made self-reflexive cameos in WarioWare, some lifted wholesale, others slapped with fresh paint to keep with a new aesthetic. The whack-a-moles in Vermin, for instance, were now claymation. The game based on Fire, on the other hand, retained the sparse, retro black and white visuals of the original. The Game & Watch was one of several nods: there were also references to GBA, NES, SNES and even that eye-ruining monstrosity, the Virtual Boy.

Regardless of WarioWare’s link to the past or future, it has firmly stamped its own unique mark in time thanks to one all-important reason: it was never boring. This was gaming without the unnecessary bits, pure nuggets of distilled fun. So while WarioWare at first seemed the furthest thing from a videogame, it ironically had more claim to the title than anything before. When you get right down to the meaning of the word ‘game’, past long cutscenes and exposition-spouting characters, past HD graphics and soul-shaking orchestral scores, it’s about a self-enclosed interactive experience. WarioWare didn’t just adhere to that definition, it embodied it, offering not just one tightly focused experience, but hundreds.