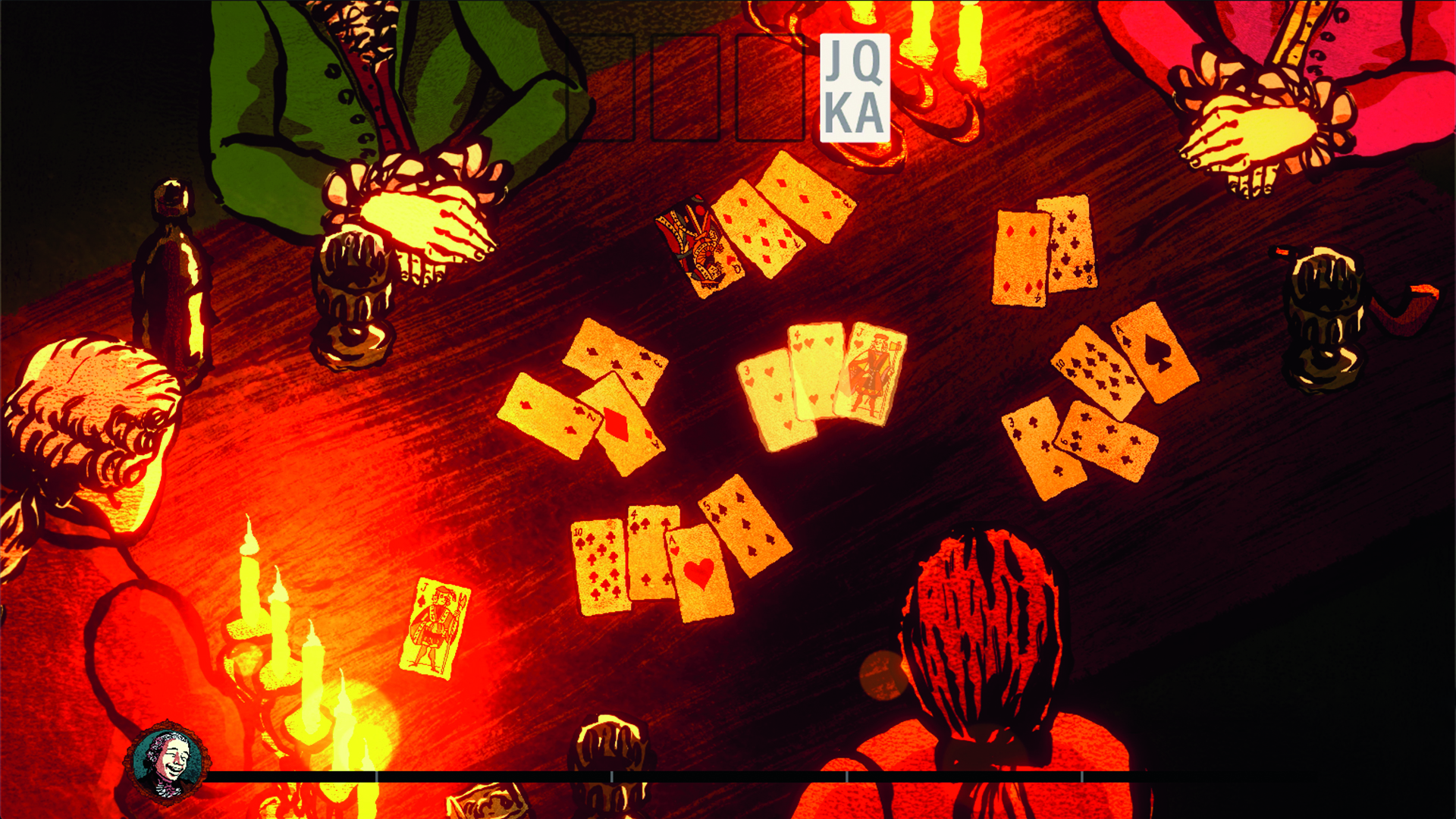

WarioWare meets Kubrick in Card Shark, a card game like no other

Card Shark is a cheat 'em up from Reigns developer Nerial

As kids we are told that cheats never prosper, a proverb that life seems to be doing its best to disprove. So why not get in on the grift? Nerial's latest is another card game, but it isn't your average deck-builder, though in a sense it shares something in common with this now-ubiquitous genre. You'll need to master a variety of techniques to cheat your way up to the upper echelons of 18th-century French society, even putting your life on the line in the highest-stakes games. But on a fundamental level, it's all about ensuring you've got the strongest hand.

The idea behind Card Shark began to form when artist and former filmmaker Nicolai Troshinsky developed a fascination with card magic. But it only became tangible after he watched Stanley Kubrick's period drama Barry Lyndon. "There's this very memorable scene where the main character cheats with cards," he says. "And that quickly connected to what I was learning at the time about card manipulation." He started researching the mechanics of card cheating in the hope of creating something that matched the sense of mischief of the scene in Kubrick's film: a playful kind of swindle.

Troshinsky was confident others would find it appealing, because the process of learning the tricks proved so enjoyable to him. "It creates a kind of loop – and it's very exciting. Like, you learn a thing, you practise it, you execute under pressure. I thought I could translate that into an interactive experience. It's exactly the same process but, of course, massively simplified, so it's fun to interact with." The fantasy, in other words, without the years of practice.

Breaking the rules

Edge is a global authority on videogame art, design and play, providing subscribers with a regular source of trusted videogames industry insight. You can subscribe to both the print or digital editions here.

Any good scam requires an accomplice, and that happens to be you. Rather than sitting at the table, in an early game you're hovering by it – as a wine server, you can peek at the hands of the other players to pass information to your colleague by wiping the table in specific ways. "You have to memorise the code, you have to perform it under pressure because you can't peek for too long, then you have to signal the correct thing," Troshinsky explains. Later games introduce other methods of subterfuge: if you don't know your opponents' cards, perhaps you can cut or shuffle the deck to ensure your partner has the best possible chance of winning.

New techniques are gradually introduced: with some you'll effectively accomplish similar goals through different means, while others raise the challenge by having you play among a more suspicious group. Troshinsky reckons there are "30 to 40" in total, likening them to more complex versions of WarioWare or Rhythm Heaven minigames, and as you move through the game, the sequences grow longer and more elaborate. For Troshinsky, it's just like learning magic. "What I realised is that there's this combination of skills – there's some memory, some counting, some manipulation skill, doing something fast – you've got all these different techniques, so there's a variety of skills you can develop."

There's strategy, too. Other players will become distrustful if you tarry while glancing over their shoulders or botch a false shuffle. But you'll be able to recover from mistakes, intentionally losing hands to avoid blowing your cover. "If you screw up midway, you can either try to rush your last few techniques to get it done and win," Troshinsky says. "Or you can sacrifice some games and try again in the next round." And should you get caught? Troshinsky says you'll be punished, but what that means in game terms is still in the balance. "Some games might result in you losing all your money, and some might result in you going in jail. Some might result in immediate death! We want you to feel the tension of the consequence of being caught. But, at the same time, we don't want people to rage quit." Reassuring to know that here, at least, there are repercussions for fraudulence.

This feature first appeared in Edge magazine. For more like it, subscribe to Edge and get the magazine delivered straight to your door or to a digital device.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Edge magazine was launched in 1993 with a mission to dig deep into the inner workings of the international videogame industry, quickly building a reputation for next-level analysis, features, interviews and reviews that holds fast nearly 30 years on.