We're still Doomed! How John Romero's FPS design rules live on in Call of Duty Modern Warfare 3

Interview | John Romero casts his mind back over the last 30 years, and looks to the future of a tried and tested genre

It's just over 30 years since Id Software launched Doom onto an unsuspecting world. Famously, the studio decided to make it available by uploading the shareware version onto the FTP site of the University of Wisconsin, immediately crashing the institution's entire network. This was just a hint of the chaos this seminal first-person shooter would wreak. Sure, Doom wasn't the first FPS and it wasn't the first game with online multiplayer, but it innovated in so many ways, it was so fast, so advanced, so imaginative, so violent, that it changed the games industry forever.

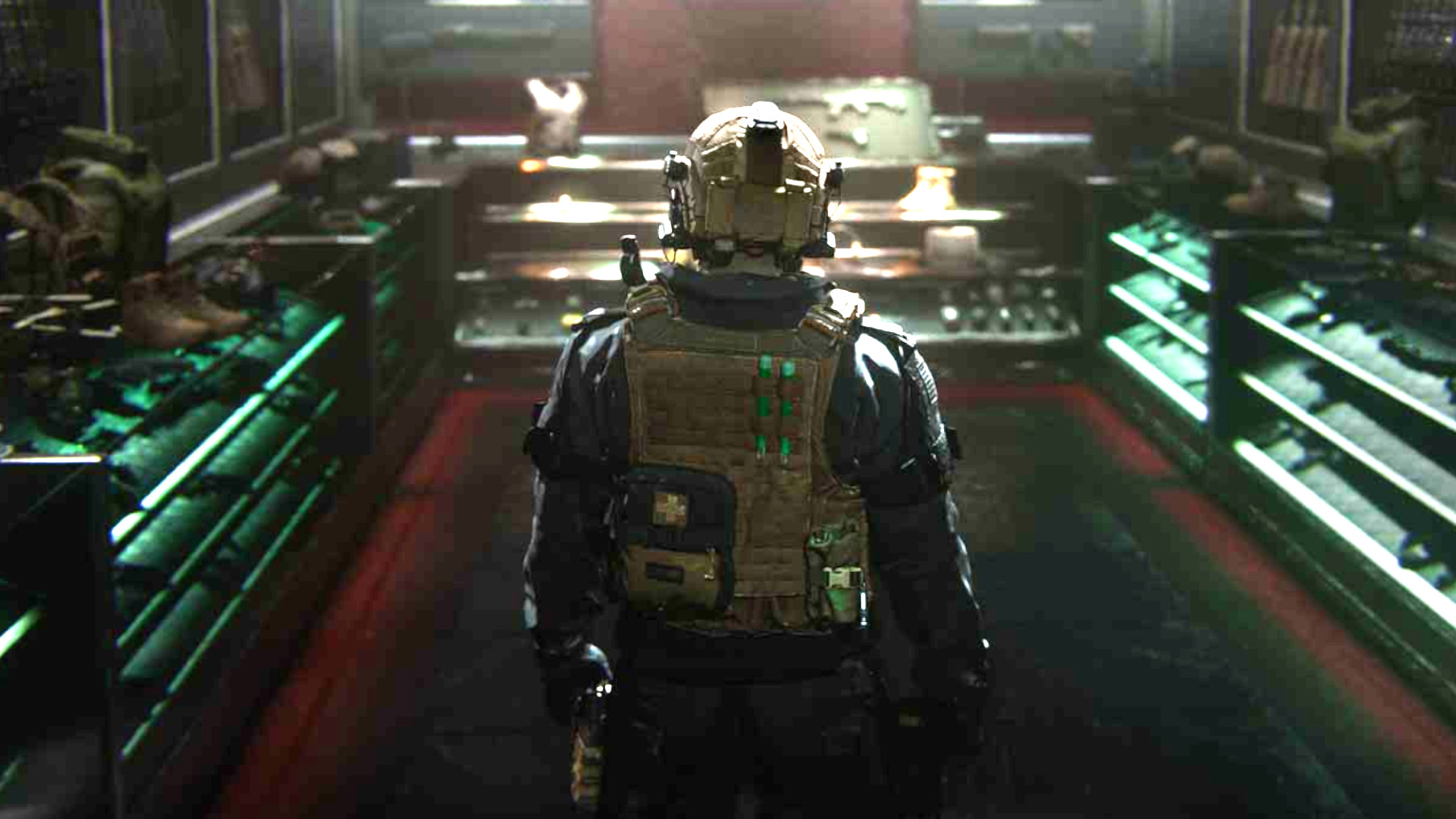

Sitting here in (almost) 2024, the age of photorealistic 4K visuals and 1GB broadband connectivity, it's tempting to believe that Doom has long since faded into irrelevance. But that's not the case. In his recent autobiography, Doom Guy, John Romero lists the set of design rules he laid out for the game while the team were working on it. Playing the very latest shooter, Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3, it's clear that most of the those rules are just as relevant to the FPS genre as they ever were way back in the mists of time (i.e. 1993) – especially in terms of online multiplayer modes. The ghost of Doom still lurks in the burned-out corridors of Modern Warfare, and I'm going to show you where.

Doom with a view

Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 review: "Stuck paying deference to a past that it seems to barely understand"

First of all, let's think about map design. Doom's levels were primarily built for the single-player experience, but they had a very compact, non-linear structure. Players often had to double-back and re-explore old areas to open locked doors. Indeed, one of Romero's Doom design rules was: "Reuse areas in the level as much as possible, as it reinforces the understanding of the space every time the player goes through an area again. For example, if players come back to a central hub before going out to a spoke, they will remember the hub the most."

While modern single-player campaigns tend to be almost entirely linear, this principle still lives on in multiplayer maps. Most are designed around two core archetypes: three-lane maps, which have a trio of parallel channels leading from one end of the map to another, and circular maps, where a central hub is surrounded by concentric orbital routes. Some maps contain elements of both.

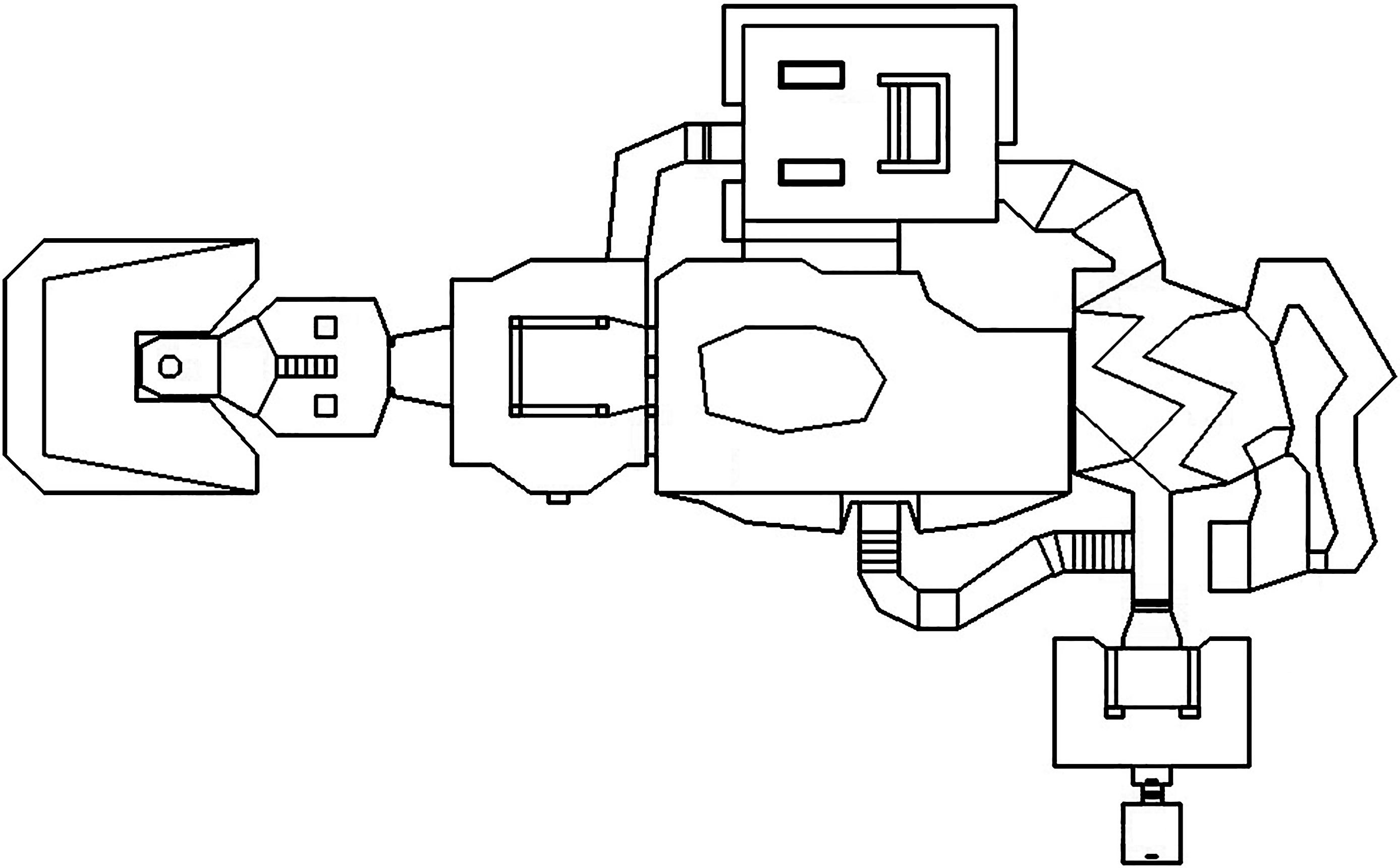

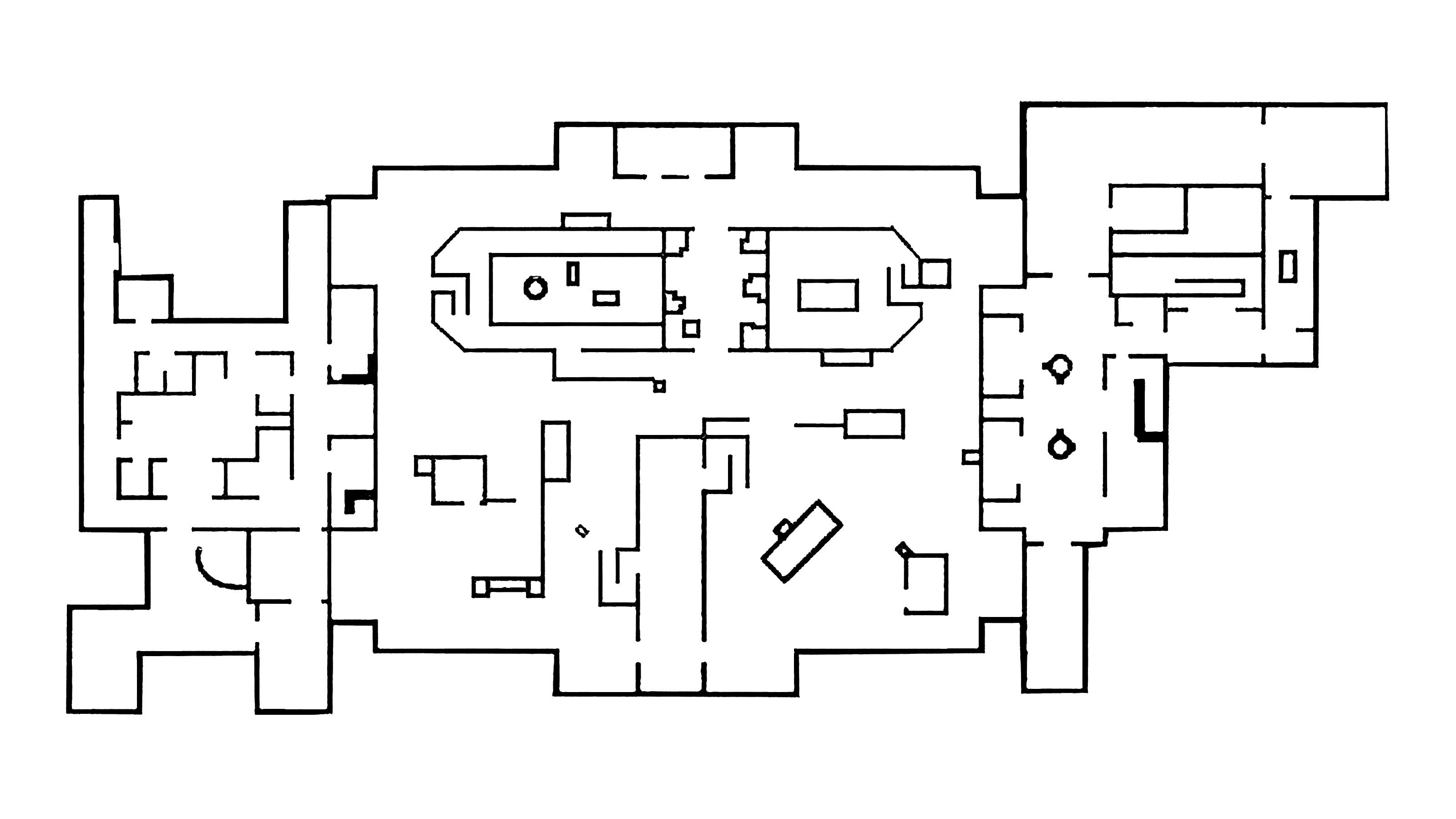

It's really interesting to look at how similar these modern maps are to Doom levels. Let's look at two examples side by side. First, we have the opening level of Doom; and second, we have Highrise from the Modern Warfare series.

Notice how they're roughly the same size, and how they both have a central hub surrounded by smaller, winding channels. Both adhere to Romero's principle of reuse, of encouraging players to memorise and constantly renegotiate the space, creating their own routes through the alleyways, tunnels and open hub sections. How we behave in MW maps is exactly what Doom speedrunners were doing 30 years ago.

One of the key principles of multiplayer map design is over-watch – the provision of hidden elevated positions with long sightlines from which cunning players can watch (and snipe) unsuspecting enemies. On Activision's Call of Duty blog, multiplayer design director Geoff Smith explained how and why these areas were reintroduced into 2019's MWII maps: "In our previous games, we would have these power positions, and those got boiled out of the game due to concerns about 'head-glitching' or camping. But that was the kind of special sauce that made Team Deathmatch work so well; that you have a power position and you actually have an advantage by having a line of sight and people would gravitate toward you."

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

This idea of gaining visibility over players elsewhere on the map was there right in the earliest stages of the Doom design process. "I remember we were barely starting to get multiplayer working," says Romero. "But I was finishing off a level design and I visualised looking through a window into another room and just thinking about two people out there throwing rockets and plasma rifle shots at each other. I thought, there's nothing that can be better than this. Blowing away a guy who's fighting another guy. We saw that the network gameplay, no matter how it's connected, was the critical must-play part of the game."

Stick 'em up

"For the re-imagined Modern Warfare maps, both Infinity Ward and Sledgehammer have prioritised fluidity of movement through 3D space."

Weapons are another area where Doom's blueprints live on. Its standard guns – the pistol, shotgun, chain gun (basically an LMG) and rocket launcher – all remain in the FPS arsenal, but more importantly, the way they were designed to fulfil different and lasting roles in the game had lasting ramifications. "Doom really expanded the vocabulary of FPSs," says Romero."It defined a lot of the rules, one of which was extremely important for all modern games, which is in the weapon selection. Every weapon in Doom is always useful.

You do not wipe out the previous gun because you got a better one. In Wolfenstein, that's not true – as soon as you get the chaingun, every other gun is useless. But in Doom, every gun is totally valuable, and that was one of the most difficult design and balancing exercises: to get the weapons different enough that you had to choose one depending on what you were doing. None are ever eliminated."

The facets that made Doom work so well are continually being rediscovered by new designers. For the re-imagined Modern Warfare maps, both Infinity Ward and Sledgehammer have prioritised fluidity of movement through 3D space. Players can climb up scenic objects such as air conditioner units onto previously inaccessible roofs, they can mantle over walls, they can slide across floors and then fire their weapons immediately, they can opt for Covert Sneakers and sprint unseen and unheard for long distances. The new games are all about uninterrupted motion.

This is exactly what John Cormack was going for when building the Doom engine. "You're always moving forward," says Romero. "It was critical that the engine was super smooth – the speed of the acceleration, the amount of friction it took to stop moving, the strafing speed, the mouse movement being rock solid. It was just the feel of the movement through that space." It's also there in Romero's first rule of multiplayer map design: "A player should not be able to get stuck in an area without the possibility of respawning."

Doom took the audio as seriously as the visual elements of the environment, and this is another vital element that still influences FPS titles today. Id Software used sound to enhance the sense of impending battles. You hear monsters before you see them, often from nearby rooms; you hear doors opening and closing. These give vital clues to the player – just as footsteps and gunshots do in Modern Warfare. Doom was one of the first games to introduce the concept of spatial audio as a strategic element.

"[It was about] setting up that environment to feel like you're under threat," says Romero. "Hearing sounds off in the distance that something is coming, that kind of thing. We had a little bit of that in Wolfenstein beforehand, but with Doom, we purposely put those wandering sounds in so players could hear them moving around and be scared to hear it. Coming up with that palette of playability and gameplay was really critical."

The chances are a majority of Modern Warfare III players have never seen the original Doom running on a 386 PC in 320 x 200 resolution – the way it looked and felt thirty years ago. But you can buy it on Steam for a couple of quid, or try the homebrew update GZDoom. Graphically, it's hopelessly dated in a lot of ways. But the feel of it – the speed, the guns, the player movement, the design of the maps, the drama of player-vs-player engagements in dark corridors – all those elements still work. The rules Romero shared with Id's designers and programmers hold up. In fact, Romero is still using them - as well as a lot of the original Doom code - in his next project, the spiritual sequel, Sigil 2. Doom is to games what Halloween is to slasher movies – an inescapable blueprint. You can run from it, but even after 30 years, you can't escape.

Here are the best FPS games you can play right now

Keith Stuart is an experienced journalist and editor. While Keith's byline can often be found here at GamesRadar+, where he writes about video games and the business that surrounds them, you'll most often find his words on how gaming intersects with technology and digital culture over at The Guardian. He's also the author of best-selling and critically acclaimed books, such as 'A Boy Made of Blocks', 'Days of Wonder', and 'The Frequency of Us'.