Why most scary games fail as real horror, and why they always have

There’s a bit at the beginning of Gears of War, appropriately referenced in our feature on inappropriate jump-scares, in which Epic’s inaugural chainsaw carnival wrong-foots you with a hint that it might be a horror game. After trekking through Marcus’ deserted, decaying prison for a little while (stock horror environment #37, fact-fans), you’re briefly accosted by the sight of some dangling, aggressively butchered corpses, complete with the customary, trite audio-sting and hammer-blunt smash-zoom.

It’s a fully paid-up bit of horror-game imagery. Zero doubt about that. But does it make Gears of War a horror game? No more than coating a horse with whipped cream turns it into a sundae. From that point on, Gears of War is a big, meaty shooter, and no mistake. Neither the grotesque nature of the Locust nor the odd dalliance with slower-paced jump-scares, Wretches and old, abandoned houses (stock horror environment #2) alters that fact by one iota.

But why isn’t Gears of War a horror game? It gives us bleak environments, thick with a sense of perpetual mourning. It gives us hideous, tough, and highly dangerous monsters to fight off. It delivers gore with the giddy aplomb of a newly graduated fireman on his first day of hose-duty. It wraps all of this in a weighty, all-pervading sense of oppression. All of these things are core tenets of horror gaming. They’re certainly elements which define many easily-recognisable entries in the canon. Resident Evil 4. Dead Space. This month’s The Evil Within.

So what’s the difference? Why do we say that Gears of War is a shooter, and that the others are horror games? You could argue that the largely one-note ferocity of Gears’ cover-based gameplay removes the fear factor sufficiently to earn the action-label most resoundingly. And you’d have a fairly decent point. Pretty cut-and-dried, right? Well no, I don’t think it is.

You see as a long-time horror aficionado in all media, I don’t find that a convincing argument at all. Because, after decades of immersion in horror, games, and horror-games, I think there’s something else at play, blurring the lines as fast as anyone can define them. Something endemic to horror gaming that, much like great Cthulhu, has been around so long, picking maliciously at the seams of the world, that we've long since stopped noticing its presence. Simply, it’s hard to define the boundaries of the horror game because very few video games have ever really delivered horror true experiences. We've pretended otherwise for a very long time, but really that’s the ugly truth.

Most horror games, even the really good ones, are games first and foremost, horror second. Strip away the aesthetic, and mechanically they’re just games. Some are actiony, some are stealthy, many dwell somewhere in between, but in truth they’re mostly just stock game mechanics painted with a gory or supernatural surface gloss. And real horror just isn’t like that. A good horror novel isn't a spy story where all the enemy agents just happen to be zombies. A good horror film isn't a generic Michael Bay movie, only set at night and full of vampires. Blade is a great, supernaturally-themed, gory action movie, but a great horror film? No.

In real horror--and this statement might sound trite upon first scan, but stick with me--the horror is the focus. In fact more than that, it’s the be-all and end-all. It’s not a tonal or aesthetic garnish for something else. It is the core of the whole experience. It’s the conduit through which all of the statements, thoughts and musings in the author’s mind are filtered in order to--as is the case with all good genre fiction--extrapolate ideas and experiences, and through their amplification, truly explore them.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

And all good horror is about something. John Carpenter’s Halloween is concerned with the progressive, hypocritical isolation of suburbia in the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Aliens is about Vietnam. Don’t Look Now is about the fatalistic nature of obsession and mourning. H.P. Lovecraft’s work, which beautifully straddles the line between art and pulp, is dripping with existential terror at arrogant mankind’s tiny pinhole view of reality. Same goes for the work of classic English novelist M.R. James.

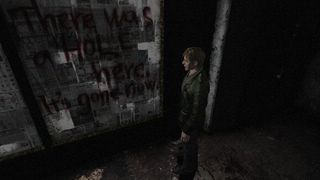

But the point is that whatever subject matter or ideology is being filtered through it, the horror is the core. It’s the engine that makes the whole affair work. It’s what wraps up and forms every part of the work. But horror games don’t usually do that. They usually just stick some scary atmospherics next to a stealth, survival or action game, and leave it at that. They’re almost always primarily concerned with servicing their gameplay mechanics, with horror coming a distant second, if at all. The last time a big, mainstream release did the real horror thing was probably during the heyday of Silent Hill.

Although seen at the time as a rival to Resident Evil, in truth Silent Hill couldn’t have been further from its gore-munching genre-buddy. Furthering my points above, while both games are ostensibly third-person survival-horror games with deliberately awkward combat, squiffy, disorienting camera angles, and an emphasis on escape and evasion, it’s not their gameplay mechanics that ultimately matter, but their tones and the narrative content.

Resident Evil, even in its earlier, less action-driven entries, was a surface-level horror rollercoaster, trading on the vital thrill of jump-scares, gore, and b-movie monsters. It was, as is often the case, more focused on gameplay systems and aesthetic than deeper, true horror. Silent Hill though, at its best, has always operated in the inverse, using its gameplay to service a greater aim. The series’ high points have always been about atmosphere, emotion, psychology, and the use of horror’s nightmarish, surreal excesses to explore deeper, more powerful concepts and notions. Its monsters are no mere bitey cannon fodder. Each is designed to evoke and reflect an element of the lead character’s trauma and internal struggle. Its twisting, reality-bending journeys are crafted to disturb in specific ways that also resonate with the above.

It’s no coincidence that the series’ weaker, later entries are the ones that, with lesser or no involvement from early series Producer Akira Yamaoka, lost track of that. Neither is it any coincidence that Yamaoka’s dual role as designer and composer was instrumental in creating a coherent, cohesive, authored, ‘total horror’ production. Silent Hill is a game, but it’s one that has more in common with the legitimate conceits of literary horror than those of its corpse-grinding stablemates.

So are we now screwed for real video game horror? Are we bereft of hope and scrabbling in the dark, with Resi literally sticking to its guns, and Yamaoka seguing toward film, now working with Italian horror master Dario Argento? Well no, we’re not. Just as I was starting to give up, and ready to resign my gaming horror activities to the mental folder labelled ‘Fun diversions, but eh’--alongside Fast and Furious films and yo-yoing--a new wave of the real stuff has started to seep insidiously through the cracks in the floorboards.

P.T., with no hyperbole, is the absolute antithesis of game-horror's failings, intelligently recognising the detrimental effect of oft-applauded player agency on the power of horrific confrontations. That it also tightly winds its horror around a carefully crafted frame of psychology and significance makes it one of the finest and most insightfully directed interactive horror experiences in years.

Alien: Isolation, despite being a more player-driven, stealth-horror experience, truly understands the impact and nature of its source material’s make-up. With that at its core, it fearlessly eschews all of gaming’s empowering, protagonist-courting safety nets and ‘necessary’ softened corners to create a savage, uncompromising simulation, made of primal terror and the unpredictability of real survival.

Perhaps ironically, given the arguments I’ve sketched out above, this resurgence is partly down to improved technology. Alien: Isolation just wouldn’t have been possible without the advanced, living, breathing artificial intelligence Creative Assembly created for the titular beast. P.T.’s atmospheric, claustrophobic, pure-horror focus is arguably amplified--and perhaps designed to show off--the near photorealism of Kojima Productions’ new Fox Engine.

But beyond technology, the human, creative factor remains all important. That mention of the studio behind Metal Gear resonates beyond the power of its shiny new toys. Horror like P.T. (and the in-production Silent Hills) requires the kind of deeper-thinking, more experimental auteurship that someone like Hideo Kojima--alongside collaborator Guillerno Del Toro--brings to a project. In fact his spiralling, fourth-wall-breaking, creative playground approach to direction will probably be far more at home on Yamaoka’s turf than it even was in MGS. Besides, a series as unique and artistic as Silent Hill needs a director with that sort of unchallengeable clout. Someone with vision and power, who can stand up for his ideas in the same way Yamaoka once did.

Similarly, if Isolation hadn’t been made by a team as dedicated to Alien detail as Creative Assembly--not just in terms of aesthetic, but also the tone, mood, and subtextual fears fundamental to Alien’s world and its violence--then it would merely be a beautiful sci-fi stealth game with a very dangerous monster.

So I suppose we come full circle. The future of video game horror simply cannot be about surface gloss, and gore, and overcoming the monstrous hordes. However much incoming visual fidelity affords us the ability to create more realistic dismemberment, and great numbers of the undead, we cannot allow horror to remain so external, a thing to be overcome with gameplay, weapons and agency.

To both the player and the creator, video game horror must, as it does in all other media, excel by becoming an internal experience, authored with thought, intent and craft, and experienced with personal resonance and uncomfortable meaning. I don’t want to jinx it. I don’t want to speak too soon. But it seems like technology, ambition, and (very probably) the more open creative climate brought about by the newfound prominence of indie gaming, might just be about to combine to create a bold new era. Horror fans, cross everything you have.

Minecraft Pocket Edition got its name because one of its devs was a big "Nintendo nerd" who wanted to pay homage to the Game Boy Pocket

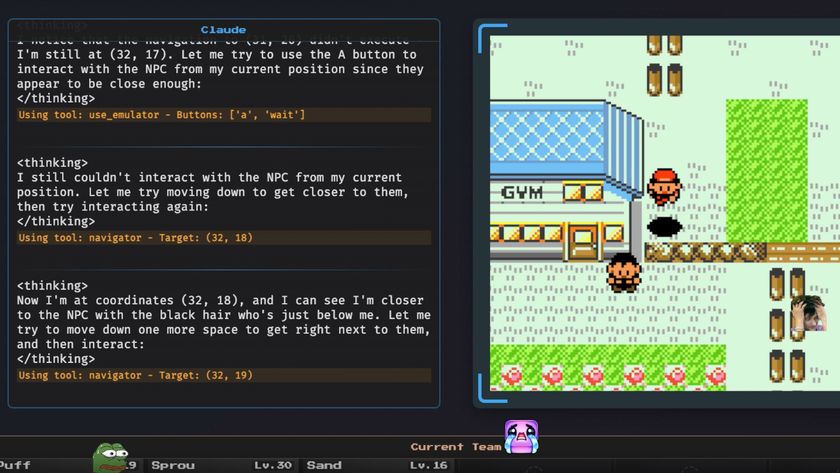

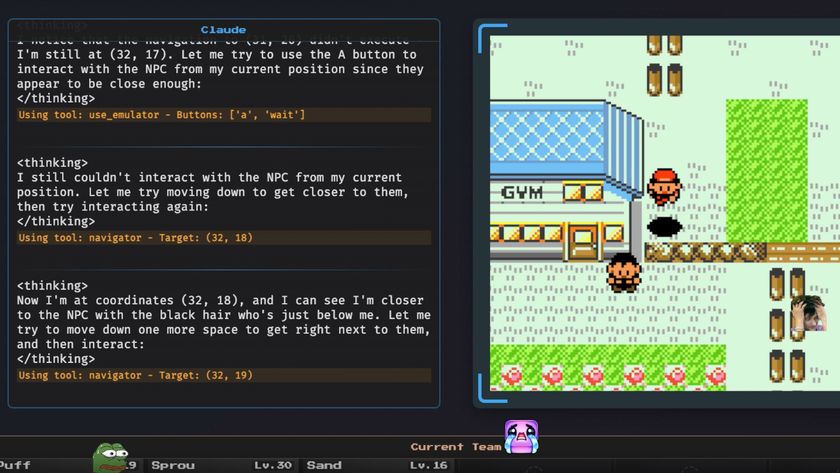

An AI's mission to 'teach' itself Pokemon Red is going as well as you think - after escaping Cerulean City after tens of hours, it went right on back