Why Prey is frontrunner for game of the year 2017

As much as we try - as is only healthy and correct - to hold off early critical judgements, and let games meander the merry path of development unsullied by early assumption and prejudice, some seem to flag up their potential pretty brazenly from the start. We're not always right, of course. For every out-of-nowhere, critical step-up like Titanfall 2, there's a surprise disappointment like Mafia 3. But, eschewing all cheap, lazy, forum snark and flailing fanboy hype from the equation, some games just set off a certain kind of signal. I called it back in January but now, two fresh demos later including the opening hour and a puzzle-heavy mid-section, Prey looks very much like one of 2017’s biggest and most important standouts. Even with the likes of Horizon: Zero Dawn and Persona 5 proving to be exceptional games.

Why? Well there are the obvious reasons of pedigree, of course. Certain studios earn the right to command confidence, and Arkane has arguably hit that stage now. Best known to the mainstream console gamer for Dishonored and last year's Dishonored 2, Arkane is the game dev supergroup when it comes to the dynamic, open-ended systemic gameplay of the emergent sim genre, its members having collectively worked on BioShock, Deus Ex, System Shock and Half-Life 2 in the past. Doing for option-laden, player-driven stealth sandboxes what Super Mario Galaxy did for the 3D platformer, Arkane's two most recent games represent a studio with decades of none-stronger insight into the fundamentals of its chosen genre, yet an uninhibited, forward-looking thirst for exploration and evolution.

That makes any simulation-driven Arkane project an exciting one, but Prey is more exciting than most. Because while Dishonored and its sequel represented Arkane evolving a genre, while also making a statement of intent about its own contemporary philosophy and capabilities, Prey seems to represent Arkane evolving itself in a way that echos the creation of some of gaming’s historical brightest and best.

Half-Life 2. Portal. Call of Duty 4. Any main-series Mario game you care to mention. Resident Evil 4. Dark Souls. BioShock. As drastically different from each other as they are, they all have a similar, spiritual feel. Because they're each the product of a brave, confident developer looking at what it knows - and what its audience likes - and asking 'But what if we could do this?’. And then dropping in a new idea that blows the doors off the original idea’s entire set of conventions.

Portal looked at the platform game, and then completely changed the player's perception of time and space. Half-Life 2 looked at the FPS, added physics, and made almost every object in its world a viable tool. Resi 4 zoomed in the survival-horror camera and turned traditional zombie-wrangling into an intense, intimate, consummately balanced feat of knife-edge crowd control, built of both scale and cerebral subtlety. Dark Souls looked at RPG melee combat, and asked 'But what if we had real duels, with fighting-game depth, as well as stats?

Prey asks 'What if BioShock was fuelled not by weapons, traps, RPG-flavoured FPS and the guided use of weird abilities, but by an unguided set of powers that we don't even want to predict, let alone control? What if we gave players not a Metroid-like set of tools for passing certain obstacles, but left our obstacles open-ended, in terms of both interpretation and solution? What if we didn’t design a set of player abilities, and then built puzzles to fit, but rather designed our world with a rough idea of how things worked, and then played around to see what was really possible? And what if we then redesigned the game on the fly to accommodate everything we could?’

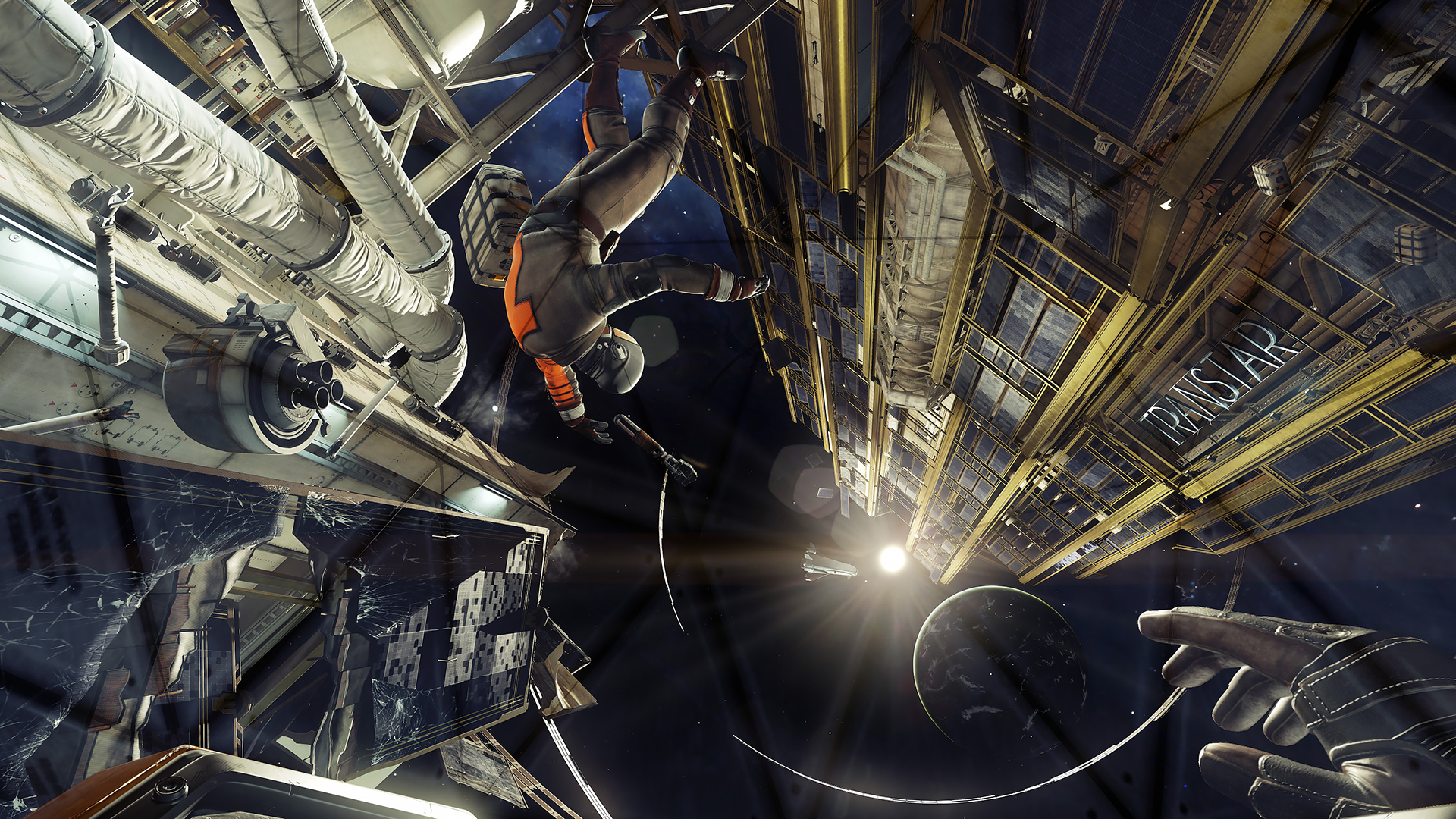

Because while clearly descended from the original BioShock, in truth the degree by which Prey is moulded by Irrational’s undersea nightmare reaches only as far as its physical template and initial scenario. We have a closed, but non-linear installation - in this case a horror-strewn space-station, which Arkane describes as one big, open dungeon. We have a confused hero thrown in at the deep end, with - initially - only the most primal objectives of ‘Survive and get out’. We have a whole lot of exotic abilities - for combat, traversal, world-manipulation, and many combinations thereof - that the player is free to adopt or not. But beyond that, right through the very fabric of its journey, the freedom of choice in its moment-to-moment choices, and how one is always the free-wheeling, immediately causal result of the other, Prey looks to be an entirely different experience.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

Remember how players were discovering new ways to use and combine Dishonored’s Void abilities long after the game was released? Remember how they realised they could summon rats, stick a mine on one of those rats, and then possess it to become a scurrying bomb? Or throw an unconscious body out of a top-floor window after a non-lethal takedown, stop time, warp down and catch it, safe and sound? Prey is taking that approach to systemic discovery, but it’s applying it to a sprawling, omni-directional, open-world playground rather than contained, controlled, semi-linear missions. It’s applying it not just to the hope of what players might discover after launch, but to how its developers are designing its systems and architecture from the off. And in Prey, you can’t just turn into a rat. You can turn into anything.

Prey is a serious step up. If Dishonored - with its previously unimagined freedom to manipulate events within distinct levels focused around handfuls of fairly clear objectives - was Arkane charting a new route through known territory, Prey feels more akin to the studio parachuting into the wilderness and trusting nothing more than its own natural ingenuity to lead it to somewhere new. It's a hell of a confident move, fueled by the kind of bravery that's mandatory if you really intend to push a medium forward.

That’s another important factor in appraising Prey’s potential. While most games - even most great games - are natural evolutions of what has gone before, the real stand-outs often have a feeling of madness, of total impossibility, about them before we play them. Hell, even for a while after. Portal dealt with a manner of thinking, and a manner of interpreting the very framework of reality, that real-life had never demanded. BioShock’s promise of free-roaming, fight them or not, fight-them-any-way-you-want bosses initially felt like an impossible dream. Half-Life 2 had a tangibility and visual fidelity that was almost too much to take in at the time. Super Mario Galaxy broke everything we knew about platforming physics, and therefor threw out every existing preconception about level design.

The reason these games felt impossible, and are such landmarks, is that they fundamentally changed the experience of what was possible in their genres. And games are about nothing if not experience. They let us think about our surroundings differently. They let us think about actions and interactions we’d otherwise never need to, or be able to. Thus, each step forward in the tools of experience takes us a bit deeper, lets us do more, lets us experience being more.

So these games existed only as exciting, abstract concepts before we played them. They were so radically, extravagantly ridiculous in their ambitions that they could only exist that way. And even having seen Prey played, a great deal now, it still feels like a similar deal. But just like the games listed above, it shares a sense that despite its seeming impossibility, there’s a tantalising, implausible sort of feasibility about it all too. I’ve seen bosses taken down in three, radically different ways, none of which felt like a canned, pre-designed solution, all of which felt like just one of many more possible approaches, using a fraction of the total skill-tree available. I’ve seen clusters of zero-g enemies taken out with stealth cloaking and careful pistol shots, but I also know that turning into a leaky explosive barrel and bounding around in a physics-driven stream of fiery death works too.

I’ve seen whole rooms remodeled and reworked with the block-building, entirely freeform GLOO Gun, traversal challenges subverted on the fly, because why both re-powering the elevator when you can just paint your own staircase on the wall? I’ve seen many, wonderful, ridiculous, impossible things, and each one has felt like only the tip of the iceberg, just for the individual challenge at hand, let alone the game as a whole. Prey feels, on a conceptual level, like madness. It feels deliberately broken, so that it can be remade and reenvisioned by the player on a whim. It feels like a game played as much by editing and redesigning the game itself as it does by, well, you know, playing it in the traditional sense. It feels like Dishonored’s philosophy of stacking, resonating, Lego-brick powers blown open in every direction, to be explored on a level not envisioned at its inception.

In short, it feels like it might be something we’ve never experienced before. And that’s why, for me, it’s leading the charge of 2017 by a mile.