Silent Hill 2 is a perfect game... and it's still inspiring survival horror today

How Konami's acclaimed horror classic embraces its technical failings to amplify the sensation of dislocation and dread

Few games have the good fortune of being perfect but, for me, Silent Hill 2 is. Now over 15 years old, everything in this dream-like tale of obsession, guilt, and desperate redemption feels deliberately placed; every aspect is perfectly intended. I'm not trying to claim that - mechanically - Silent Hill 2 is the pinnacle of video game development. Far from it. However, as the game's themes so comfortably align with the technology on which it was created, and because the content has been so carefully curated, this is one of the rare examples of a title that few would change in any way. And it's still inspiring horror games like the recent Resident Evil 2 Remake to this day. Why is it perfect? Well, it's a bit of a cheat, actually.

Silent Hill 2 actually shares a close connection with Assassin's Creed, which is far from a horror experience (unless you saw that inside-out faces bug in Unity). Both these games have created convenient excuses for their shortcomings, making them masterful examples of gaming design. Assassin's Creed has the Animus - a virtual reality system that the game's hero uses for the bulk of the action. It's a convenient way to explain things like on-screen health bars, endless retries, and invisible walls - classic gaming tropes we take for granted that simply wouldn't be acceptable in the real world. By telling players that their hero is playing 'a game within a game' Ubisoft carefully sidesteps the less realistic elements of their story (and any unintentional bugs) to craft a narrative that contains an extra layer of authenticity; that feels closer to the player's real world. We've even seen Ubi take it a step further, by positioning Animus maker Abstergo as a real company.

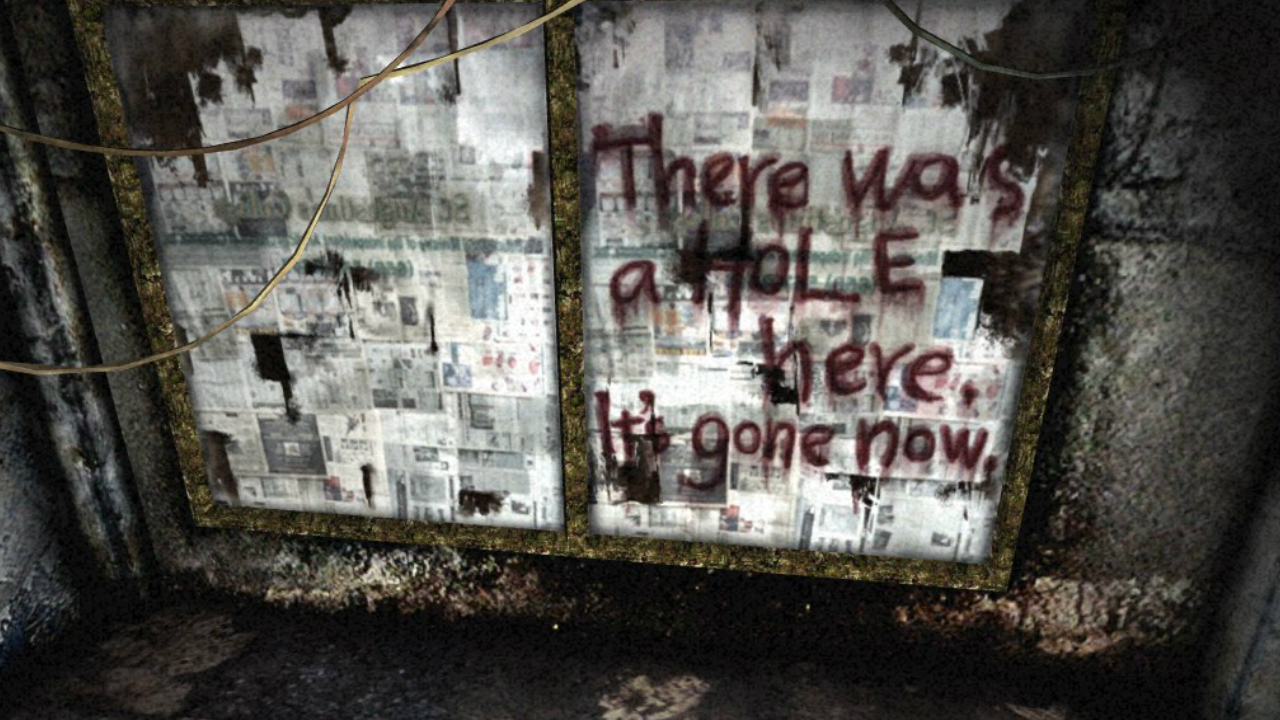

In a bizarre way, Silent Hill 2 does the same thing. The game has a dream-like quality. Nothing about it seems real to begin with. It all starts with protagonist James Sunderland pondering his reflection in a filthy bathroom mirror (a smart nod to the overarching theme of self-discovery, and maybe a cheeky reference to the eyes being the window to the soul), immediately forcing the player to acknowledge who they're taking control of. They instantly become part of James' nightmare, and from then on anything that happens does so within the context of this state of unreality. As you descend the overly-long pathway into town, you're slipping deeper in James' nightmare. Once you accept this, any number of technical shortcomings can be written off as part of the bizarre dream that the game exists within.

Bit flimsy? Well, it goes a little deeper, thanks to a handful of happy coincidences (no, I don't know the collective noun for a 'happy coincidence') and smart slices of design. First off - the fog. Silent Hill 2 was created on a console (PS2) with a relatively limited draw distance, so instead of rendering the whole town as far as the eye can see, technical limits forced the developers to blanket it with a murky shroud of mist. I say 'forced' - chances are the team was happy to do it, because there's something deeply unsettling about hearing creatures shuffling around in the haze. The bulk of the horror then takes place in the player's imagination, as they wonder what abomination will come shuffling out.

Guess what? The fog is now an integral part of the game. When it was thinned for the HD remakes on PS3/360 it actually lessened the experience. Same applies to the now out-dated controls. To fight, you need to pull a trigger, aim, and press a button on the pad. The effect is always underwhelming, as if the game is deliberately making you feel helpless. Which you are. James is just a normal (well...) guy, not a soldier or a ninja. He's pathetic in a fight. And when you try to run, the original 'tank' controls and fixed camera angles make it awkward, annoying. As the player, you're meant to feel weak; at the mercy of the monsters which may - or may not - be all in your mind.

To an extent, Resident Evil 7 plays with similar feelings of helplessness. You're locked to first-person, forcing you to live within the horror and never detach from it. Play in VR, and that gets taken to a whole new level. It's another example of creators thinking about the benefits and limits of current technology, and bending it to make the player feel vulnerable in the face of otherworldly terror. PT? Kojima deliberately used the downloadable demo format (so, a small area ripe for repeated exploration) to ratchet tension and slowly unfold a story over the course of several hours. It's smart use of existing tech and expectations.

Now, you're probably thinking that I'm making excuses for Silent Hill 2. Perhaps, but the quantity of deliberate nods from the developer blurs the line between intentional and accidental. Maybe the controls are just crappy. Maybe all the doors are locked because they couldn't be bothered to render more rooms, and not (as I'd suggest) to reinforce that panicked feeling of disorientation and inability to escape. Maybe. So why, then, does the game delight in messing with you in other ways? Like the way it changes the ending dependent on seemingly innocuous details within the game? For example, if you spend most of your time with health below 50%, you'll get the 'Water' ending, where James commits suicide by driving his car into Toluca Lake. It's the creators assuming that you don't care for your own life if you can't be bothered to heal. And what about the dead guy in the Wood Side apartments, who looks an awful lot like James? There are too many examples of smart game design to dismiss the shortcomings as deliberately clumsy.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

And then there's Maria. She's the pivot on which the game (un)balances; the physical manifestation of James' desires; the woman he always wished Mary (his dead wife) was. Her constant disappearing and reappearing act keeps the player disoriented, while the threat of the unkillable Pyramid Head (yeah, he's the physical manifestation of James' guilt) keeps them on edge. You never feel comfortable playing this game. It's a potent combination, but one that remains undulled by time. Because now - as back in 2001 - you're just as helpless and bewildered. In fact, because modern games have increasingly veered towards hand-holding and pandering to power fantasies, it's even more refreshing to find one that deliberately wants to punish its players. We've grown accustomed to being treated like the hero, not the villain, and this only magnifies Silent Hill 2's vile devices and themes.

Again, Resident Evil 7 - by rebooting the increasingly gung-ho franchise - takes us away from the power fantasy we see in other games. While we're by no means helpless in Resi 7, there's never a sense that you're over-powered and comfortable, and this is at the root of great horror. Same with Outlast. These games follow Silent Hill 2's example of making players feel uncomfortable with themselves (and often helpless) while they progress. It's a smart trick.

Resi 7 too plays with notions about 'who the bad guy really is', using it to throw you off balance. In a mirror image of Silent Hill 2's 'you start out thinking you're the good guy, but you're actually the villain', Resi 7 immediately presents you with the stereotypical baddos you expect, before turning that notion on its head half way through. No spoilers here, but you know who I'm talking about.

A perfect game, then. Not one that creates an unimpeachable utopia that's 100% guaranteed to delight anyone who plays it (can that ever truly exist?), but a grim, unrelentingly uncomfortable descent through one man's nightmare, where everything bad or frustrating happens as part of the overall experience. Embracing imperfection, steering into the skid, is perhaps the only way a game can be perfect, and that's Silent Hill 2's true, dark brilliance. Even today, as the Silent Hill series passes its 20th anniversary.