Why Wonder Woman is "the perfect queer character"

George Pérez, Phil Jimenez, Greg Rucka, and more look into the queerness of DC's Wonder Woman

The original version of this story was published in July of 2014. With DC in the midst of a celebration of Wonder Woman's 80th anniversary, Newsarama is taking a look back at a dynamic that might be as relevant today or even moreso than it was then.

If you take a look at any grammar school playground at recess and you'll probably see a bevy of first and second-grade girls with Wonder Woman sneakers and backpacks. It goes almost without saying: Wonder Woman is a merchandising gold mine for DC and its parent company WarnerMedia, and the sweet spot of that ample marketing demo is young girls and the moms and dads who buy T-shirts at Target.

But then also take a look at Christopher Street in New York City or the Castro in San Francisco, the 'Boy's Town' of West Hollywood, and you'll find an equally dedicated, but maybe a less obvious marketable fan base. It also goes without saying: Wonder Woman is wickedly popular among… gay men.

Does it seem odd? That a 75-year-old comic book character would find two such disparate audiences, with seemingly so little in common? Sure, a little. But then you need to consider Wonder Woman is one of the most unique characters in comic book history.

Wonder Woman as 'The Other'

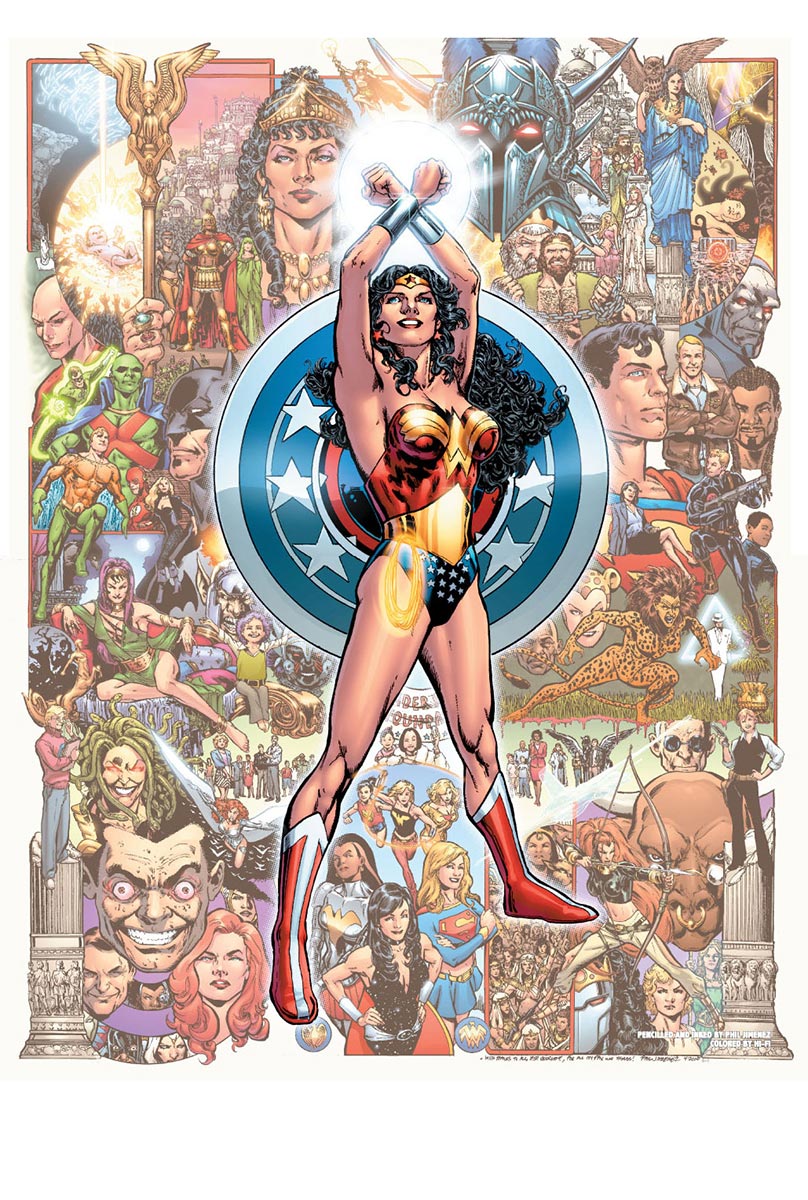

"I think Wonder Woman is, in political or philosophical terms, the perfect representation of 'The Other,' not one's self and somehow different," says former Wonder Woman writer/artist Phil Jimenez. "I actually call her the perfect queer character, and I use 'queer' in the larger, cultural sense here, not simply gay."

Jimenez should know and know in great depth. Not only did he write and draw Wonder Woman for two years from 2001-03, but he's been one of the most high-profile gay comic creators in the industry, with a rich field of work over a 25-plus-year career.

Wonder Woman is an easy "Other" in the comic book world, as there is a dearth of female lead characters. And, even as the total audience gets more diverse with every passing day, the old-school base of heavy consumers remains an audience that…the character is just not built for.

Comic deals, prizes and latest news

Get the best comic news, insights, opinions, analysis and more!

"I think one of Wonder Woman's 'problems,' and I use that word in finger quotes, is that she's not made for straight men," Jimenez says. "She's anti-assimilationist, anti-patriarchy, and definitely just not normal. Over the decades, I think one of the reasons she appealed to women and so many minorities, and yes, to gay men, is because she's the de facto representative of that queerness."

Just how queer? She might even be uncomfortable in her own skin. On the surface, the character looks like the very epitome of womanhood, a Vogue cover-ready bombshell. Underneath, she might be a man.

Christina Blanch is a graduate student in anthropology finishing her dissertation at Ball State University who has also taught 'Gender Through Comic Books' and 'Social Issues Through Comic Books' as online courses. Under the microscope of academia, Wonder Woman tests out differently than Wonder 'woman.'

"In my 'Gender Through Comic Books' course, we put her and other characters through the Bem Sex Role Inventory Test," Blanch says.

The test was developed in the '70s by psychologist Sandra Bem, and measures how masculine, feminine, or androgynous someone is by taking certain terms applied to someone and ranking them from 1 through 7. How'd the experiment work in Blanch's class?

"Batman came out of the test very masculine, Superman got almost feminine, and Wonder Woman got masculine because she has a lot of qualities that American culture considers masculine qualities," she says. "I don't think she's meant to come across as masculine, but the qualities she exhibits, we identify as masculine."

George Pérez tried to address the feminine. Pérez wrote Wonder Woman for a celebrated five-year run from 1987-92. He thinks a one-size-fits-all mentality, when it creeps in, is problematic.

"I think one of the problems that comics has in dealing with superheroines is that they try to hard to make them superheroes," he says. "All they're doing is the same thing that men do. Just the idea that they're no different that men, except in how they look, always seemed a bit off to me. The difference between Superman and Wonder Woman is not strength, or power level, or origin, but the fact that she is a woman."

Pérez set out to make Wonder Woman a book that women would like…and hopefully everyone else as well.

"At the time I started, not a single woman at DC Comics liked the book," he says. "I insisted on having a female editor to police me, and police the book. I figured if I could please her, and make her proud of the character, then I was doing a good job and providing a proper role model."

Pérez was lucky in that Karen Berger, one of comics' all-time top gun editors, got the book. The title flourished under their direction. So much so, that a young Phil Jimenez read and enjoyed the book, developing an artistic style very close to Pérez' own.

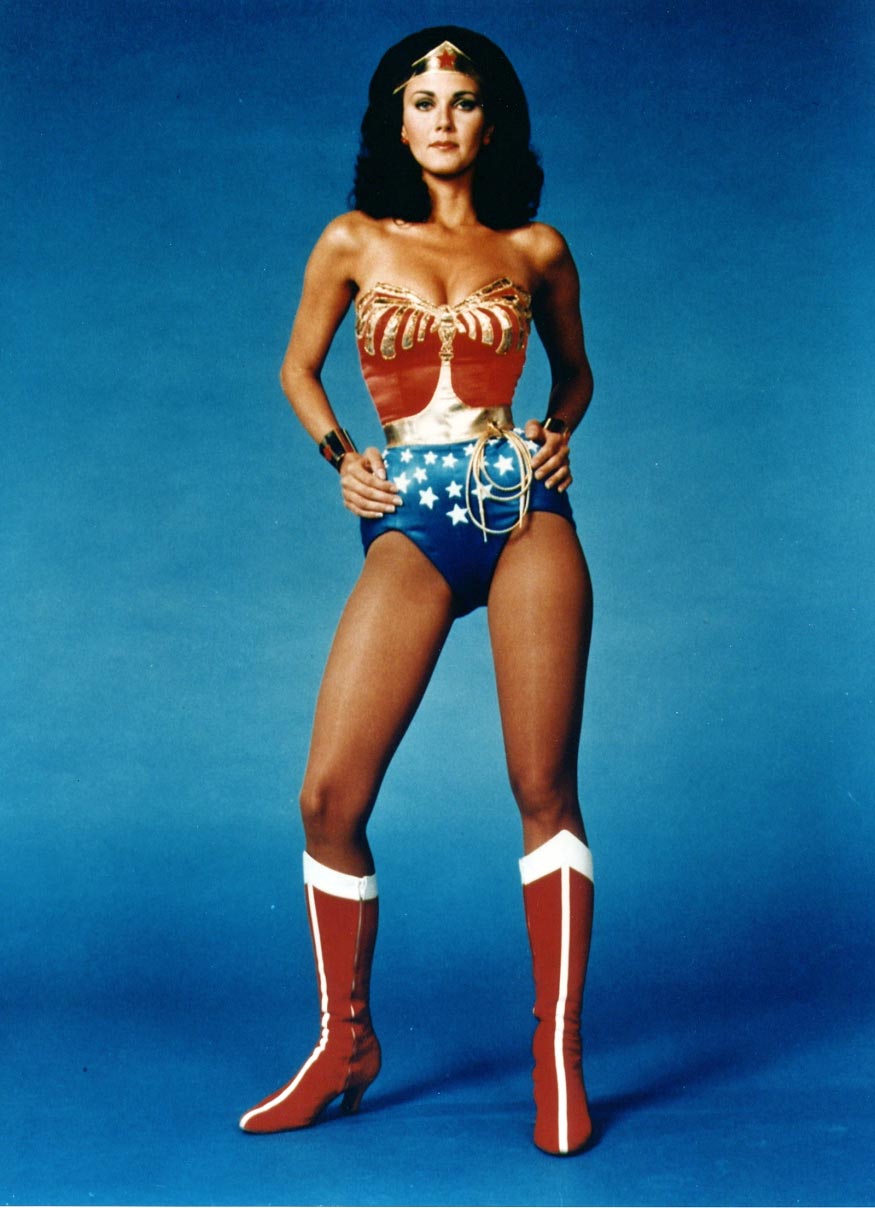

"I think there are two definitive versions of Wonder Woman: The Lynda Carter version and the George Pérez version. Those two versions have defined Wonder Woman for the past 30 years," Jimenez says today. "I think she became a gay icon with Lynda Carter."

The two Wonder Women

Ah, Lynda Carter. The beauty queen actress portrayed the character in the Wonder Woman TV series that ran on ABC from 1975-79. The series had a hardcore cult following despite a certain campiness and has a lasting impression to this day.

Diana Knight is a 34-year-old fetish model and lifelong Wonder Woman fan who loves the fact that she "can make a living fetishizing the character." She agrees with Jimenez as to who the two most important people in Wonder Woman's 'life' are. And she also thinks their articulations result in two very distinct characters.

"There's George Pérez Wonder Woman and there's Lynda Carter Wonder Woman," Knight says. "The empowered, positive role model for women is the Pérez version. It's that version that women, and some men, can get on board with."

"The Lynda Carter version appeals to gay men and fetishists because it is the super-feminine fetishized version of the character," Knight continues. "I mean, and I can't stress this enough, you really can't run in heels! That's a pure fetish/fantasy."

Jimenez thinks Lynda Carter's appeal with gay men goes at least one layer deeper.

"I think the glamorous, camp aspects of the Lynda Carter character—along with her earnestness—are what appeal to gay men," he says. "There's nothing that makes a 30- or 40-something gay man happier than seeing a Lynda Carter montage in a gay bar where she's spinning. They just get it—the transformative quality of it, an ugly duckling becoming the beautiful swan after a glamorous spin. That's an amazingly important part of her appeal to gay men."

Because, perhaps, gay men can identify with transformation and a longing to be something different.

"I do know that being the only gay guy in a group of fanboys all throughout high school and hearing them talk about Lynda Carter's body, you do feel that sense of otherness," says Mark Waters, a 40-year old billing associate for a media company and a 30-year comic reader. Waters enjoyed his time with his high school friends and found at least some identification with Wonder Woman.

"Wonder Woman had a romantic relationship with Steve Trevor that she never consummated, at least that we know of," Waters says. "And that's very similar to growing up and having crushes on your male friends that you'll never be able to fulfill. You can grow up with them, have adventures with them, but you can't act on how you really feel."

Wonder Woman can become a focal point for young gays. Sam Hatmaker, a 39-year-old toy designer from New York, was introduced to Wonder Woman from the TV show and calls her, "the first character I really connected with. It was like a first love. They say the first love is always the strongest one, right?"

Hatmaker's love goes more than skin deep. Today, he has what he calls "a giant collection of Wonder Woman stuff that takes up an entire room in my apartment. It became an obsession."

He also has the scar.

"12 stitches when I was five years old," he says. "I was in the bathtub, and it was eight o'clock at night, and the show was going to start. And I was like, 'Oh, the Wonder Woman show is on!' and I jumped out of the tub and spun around like I was Wonder Woman. I slipped on the wet tiles and cracked my chin across the tub. I had to go to the hospital. My mom said I cried the whole way to the hospital, not because I was hurt, but because I was missing the show."

The TV show exposed Wonder Woman to a wider audience than the comics had ever enjoyed, and in effect, created a second Wonder Woman. The coexistence of comic book Wonder Woman and Lynda Carter Wonder Woman can create friction, even among those who have enjoyed both.

"The TV show plays so much of an integral part of her popularity among gay men, but it's problematic as well," Mark Waters says. "I just rolled my eyes when Phil Jimenez put so much of the TV show in—he had her spin and even put her in the diving costume [seen in the TV show], for Christ's sake. I mean, goddammit, the TV show is not the comic book story."

Still, the impact that the TV show had cannot be denied.

"I have a very good friend who had Lynda Carter autograph his arm, and then he got it tattooed," Waters relays. "She talked about it on E! Entertainment News. That's the gay trifecta! He got the autograph, he got the tattoo, and he got mentioned on E!"

Must… buy… two… copies!

As a publishing entity, Wonder Woman has occupied a strange space. The character was created outside the walls of National Periodical Publications (now DC), and as such, for many years, DC has needed to publish a Wonder Woman-titled series from time to time, lest the rights revert to the estate of the character's creator, William Marston. Some fans have felt that a Wonder Woman title has often been 'just thrown out there' to keep the future publishing rights alive. If fans are honest with themselves, many agree that the entire era from the '60s through George Pérez's arrival in 1987 was a wasteland.

"I barely read it. Maybe a single issue or two," Pérez says. "I grew up on comics in the '60s era, when Wonder Woman was rather silly. She was an interchangeable female character plagued by bad stereotypes. She cried at the drop of a hat, she was worried about how she looked, all of that."

Pérez looked across the aisle at Marvel for inspiration.

"When they gave me Wonder Woman, I wanted to do a fantasy character, a la what Walt Simonson was doing—brilliantly!—with Thor and Norse mythology. I wanted to tap into it with Wonder Woman's mythological background, which, fortunately, hadn't been touched very much. I wanted to do a Ray Harryhausen story with Wonder Woman as the lead."

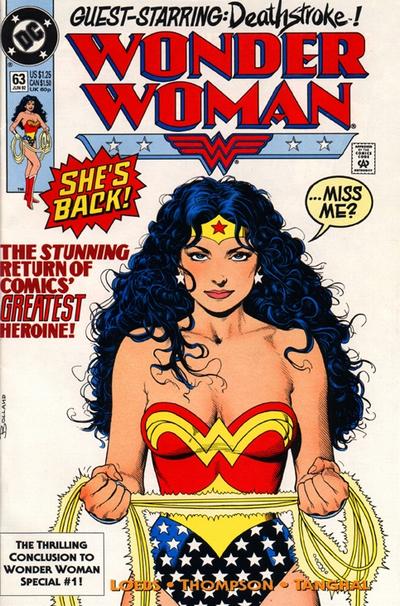

The direction worked, as long as the vision was there. But with Pérez' departure in 1992 came the seemingly inevitable Wonder Woman drift. Is she a warrior? An ambassador? The female Superman? Do we need a costume change (again)? No one seemed to know. But the imperative to keep publishing something led to a mish-mash of a character.

"Hey, I was always more of a Black Canary fan," says Mark Waters. "Wonder Woman is just higher-profile. I enjoyed the TV show and whatnot. But she never seemed…all that well-defined, I guess."

Phil Jimenez tends to agree.

"A number of times, Wonder Woman's runs have been tinkered with, adjusted or aborted in an attempt to adjust for sales to an audience she ultimately doesn't appeal to," he says. "They're constantly looking for a way to make her saleable to an audience that she's never going to appeal to anyway. The successful Wonder Woman runs, like those from George Pérez or Brian Azzarrello, seem to be the ones where there's long and consistent editorial support behind them so they can create and sustain a vision."

But even when the book is 'bad,' Wonder Woman maintains a hardcore audience, for reasons that may seem strange.

"A lot of my gay friends are afraid to speak up, thinking if they say anything bad, maybe they won't publish her anymore," Jimenez says. "I don't know if that's true, but I know people who buy two copies every month even though they don't like it, for fear that any issue could be Wonder Woman's last chance."

Mark Waters sees much of the same.

"The comics have never known what to do with her," he says. "I think that if DC could get away with having her in a team book with no solo title, they'd do it. They just don't know what to do with her."

The costume, the costume, the costume… and sex.

Comic book characters change costumes. It happens. More often than not, it's a minor blip. But when it happens with Wonder Woman, it's a Women's Wear Daily-level emergency.

"Every year at the Gay Panel at [Comic-Con International: San Diego], there's this couple—two guys, at least I think they're a couple—and year after year, they ask the same fucking question: 'When are you going to put Wonder Woman back into heels?'" Mark Waters relays. "Would you please tell me why that's important? I just don't know! But gay fans are much more rabid about Wonder Woman than, I think, the most strident straight fan of Batman could ever be."

Bottom line, anytime DC messes with the basic Wonder Woman costume—yes, the one worn by Lynda Carter—they're micro-analyzed to the point of distraction. See the on-again, off-again from 'The New 52' relaunch in 2011 for a ready example.

"There were gay men who were offended that [cover artist] Adam Hughes, no matter how wonderful his drawings looked, put her in those big, floppy boots," Waters says. "You change one iota of Wonder Woman's costume and you hear about it from gay men."

It's not like Superman's costume would make much 'sense' in the real world either, but questions of practicality inevitably come into play with Wonder Woman's costume, seemingly in disproportionate numbers.

"Yeah, screw those guys that are always asking about the heels," Diana Knight says. "One of the best things George Pérez ever did was take that heel off. I love heels as much as the next girlie-girl or drag queen, but not if I'm gonna go out and fight crime in them. And all due respect, Lynda Carter couldn't run in heels, either. That's why there are all those cheesy change shots with her running in flats."

Phil Jimenez sees a split along gender lines when it comes to Wonder Woman's costume.

"I think women—and you don't have to be 'comic women,' I mean my cousins, people I meet on the street and girls on Halloween—are not overly concerned with the costume," he says. "They think it's just fun. And maybe flashy and kind of silly, and maybe a little sexy in its way."

But Jimenez sees a change in attitude on the other side of the aisle.

"The costume's sexualized aspects, I think, make straight men uncomfortable," he says. "They see it, and they don't want to explain to their kids the kinds of feelings it might bring out in them…which are probably the same feelings they're having themselves. But I think gay men don't have those feelings, and therefore they love the costume."

And think about this: The hyper-sexualized costume is worn by an effectively sexless being. Not that George Pérez didn't give the subject some serious thought.

"I would have love to have handled a sexual storyline," Pérez says. "It's an island full of Amazons, so of course, there were probably a few homosexual relationships there. Some might have chosen celibacy, but I'm sure some would look for sexual congress in the company of a like-minded person. But this was comics in the '80s. I knew it was a battle I could fight to do it, but I didn't think I could win. So I just kept it on the sidelines, tried to sneak a little in."

The feminist piece of the Wonder Woman puzzle

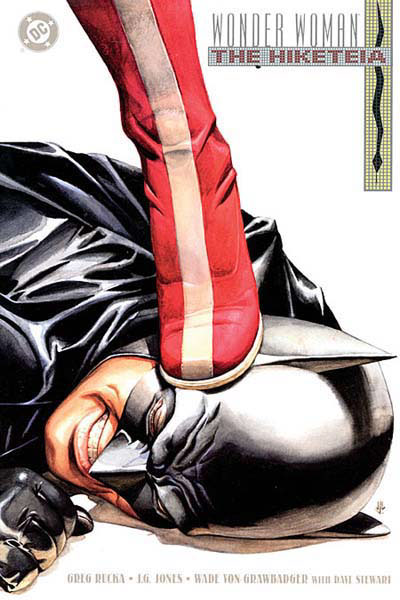

Christina Blanch is quick to point out there's another audience for Wonder Woman as well—feminists. And Wonder Woman has had at least one writer who trumpets the fact that he's a feminist very loudly, Greg Rucka, who wrote the book from 2003-2006.

"Wonder Woman was designed to be a feminist character by a man [William Marston] who had, for the times, some very progressive attitudes toward feminism and gender equality," Rucka says. "His thoughts on women certainly crossed over into fetishizing, but it doesn't change the root fact that he was writing a feminist character. She's meant to represent, if not a superiority as she's an Amazon, certainly the equality of women."

Rucka feels the character is inherently political, and it's his job to bring those politics to the fore.

"I believe that when you write a polemic, nobody wants to listen. Nobody wants to be lectured to," he says. "But good art requires some amount of commentary. And what she believes is important. The politics can help drive the drama."

During Rucka's first run, Wonder Woman became the ambassador to the United Nations from her home island of Themyscira. "Diana's origin, in part, is about her leaving a feminist's paradise to come to a patriarchy to try to educate it," he says. "Changing minds is a massive part of her mission. But as feminism changes, the goal of that mission changes."

The fluid nature of society, oddly, creates a character whose origins are not set in stone, but fluid as well. "What it means to be a feminist is very different today than what it was 70 years ago when the character was created," Rucka says. "So she changes in a way that really, no other superhero does. The roots, origin, and core mythology of the character become very slippery as society changes."

Regardless, Rucka and others believe that Wonder Woman's bearing is unique.

"She's a presence," Rucka says. "She's a Greek demigod who's also a superhero and has an active political life. I wanted to touch on the fact that meeting her was like meeting Gandhi, the Dali Lama. She has great physical power, but also great grace."

No surprise, much of what Rucka feels are echoes of George Pérez's run.

"Her mission is one to serve mankind by making it better," Pérez says. "I didn't treat her like a feminist: I treated her like a humanist. You can't help but feel you need to be better when you're around Wonder Woman. You need to be strong. You need to accept yourself and everyone around you. You need to be worthy."

Christina Blanch sees that side of the coin but also sees a Ken-and-Barbie projection, perhaps the opposite of a feminist root, thrown on the character.

"Like right now, they're trying to have her in a relationship with Superman to make her more relatable," Blanch says. "I think that's been the fan fiction forever, right? Superman and Wonder Woman together? I think in comic books, females are almost required to be there as a response to a male counterpart. I think that's just one of the things still in our culture—'A woman needs a man.'"

And in the end

Is Wonder Woman indeed "the perfect queer character"? A vessel for Lynda Carter? A feminist icon? The character is certainly one thing.

"She's a symbol for sure, because there really isn't anyone else out there," Christina Blanch says. "There's been no other superhero for eight-year-old girls. It's just recently that there's a Ms. Marvel or the Black Widow, but there's no presence like there is for Wonder Woman. It's not like you can go to a Target or a Wal-Mart and find female characters other than Wonder Woman. You get Wonder Woman and nothing else."

Second-grade girls and gay men are an incongruent combination. But it's not like DC Comics, or anyone for that matter, chose these as the target audiences. Rather, perhaps the target chose the arrow.

"When I did Wonder Woman, I was especially proud that I had both a very large straight female and gay male following," George Pérez says. "One of the greatest compliments I ever received on Wonder Woman was from a woman who read it, and was genuinely surprised that it was written by a man."

And Pérez said his approach was as broad-based as possible.

"I wasn't trying for a boy audience, a girl audience, a gay audience, any of it," he says. "For every gay fan of my Wonder Woman I seem to have, I have just as many women, or straight men. I wasn't pandering. I was just trying to write a strong woman. I'm still surprised, 20 years after the fact, that people tell me they like it."

And maybe, in the end, the broad base is the only base.

"I think she winds up serving many purposes, and perhaps because of that, that's why—pick one—people say DC doesn't know what to do with the character, or they haven't made a movie with her yet, or why a lot of writers aren't sure what to do with her," Blanch says. "People are always trying to walk a fine line with her, not going strongly one way or another. Maybe she doesn't have to be a representation of every woman—she's just Wonder Woman."

Wonder Woman may be the "perfect queer character," but in comic books, she's just one of many great LGBTQ superheroes.

—Similar articles of this ilk are archived on a crummy-looking blog. You can also follow @McLauchlin on Twitter