Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom's best world-building feature is something I normally hate in video games

Opinion | In Tears of the Kingdom, familiarity breeds content

I'm playing The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, and all I can think about is Silent Hill 4: The Room. Two very different games, I'm sure you'll agree, launched in two very different eras within two very different genres. But if you'll allow me a quick tangent I'll explain.

Even if you've only a passing interest in survival horror, you'll likely have heard fans of the genre waxing lyrical about Silent Hill's second outing. 'Silent Hill 2 is a perfect game' is not an uncommon opinion among scare 'em up devotees. And while I myself am very fond of James Sutherland's twisted misadventure in the titular cursed town, I also firmly believe the game's indirect sequel, 2004's Silent Hill 4: The Room, is the best of the longstanding – and soon to be revitalized – series.

In my eyes, Silent Hill 4 is almost perfect. It's unique, acutely terrifying and psychologically unsettling, but it's also let down by an arbitrary stretch of backtracking in the game's final third. With no other option, you're forced to retread old ground in order to progress the story, through levels you'd once rid of otherworldly baddies in a grind that nearly turned me away altogether at the time. I cannot stand backtracking in video games, and yet, doing so in Tears of the Kingdom while revisiting a familiar location is one of its best features.

Same place, new grace

The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom review – "A rich, robust experience that builds on what came before"

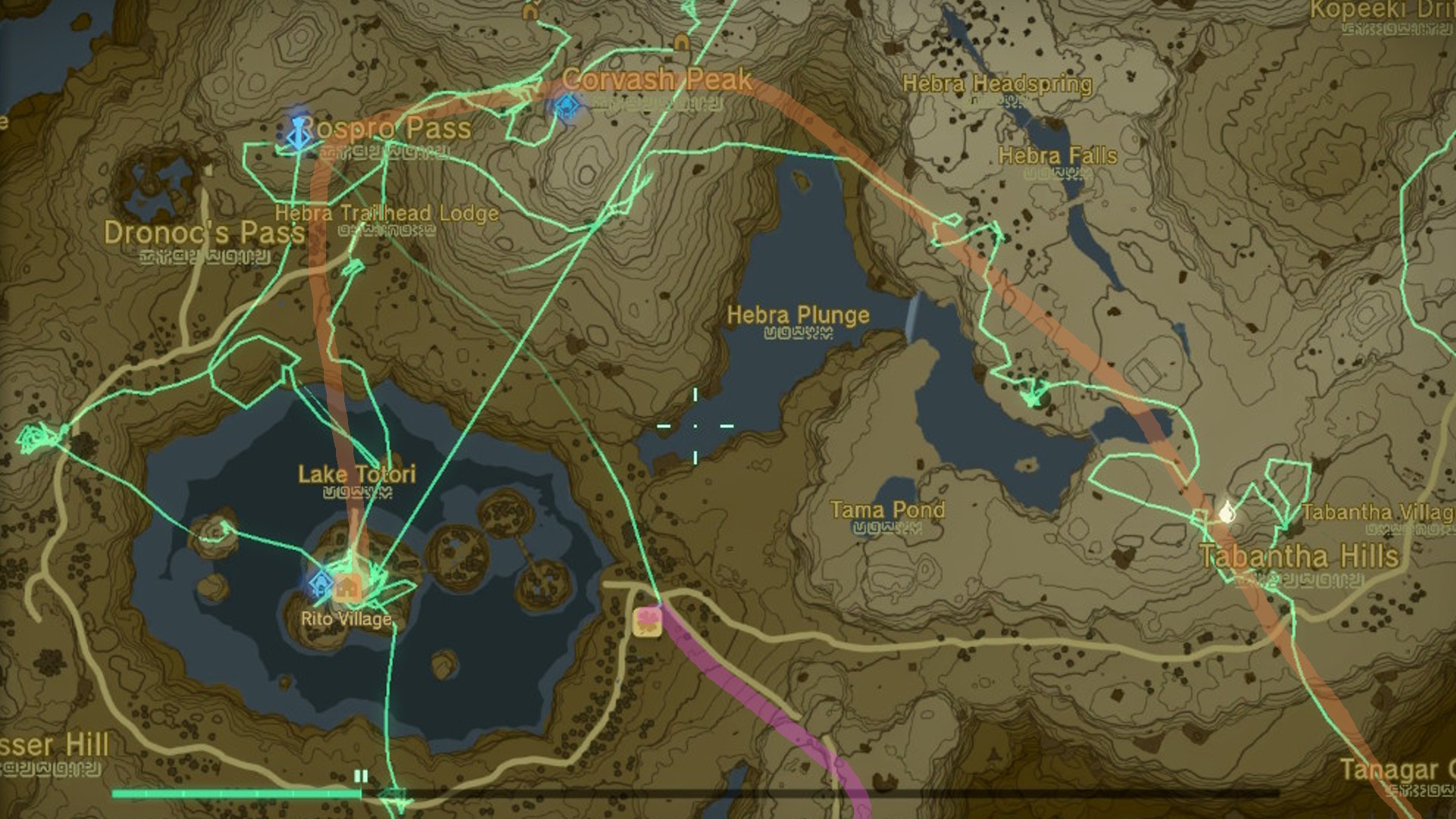

Like most Zelda enthusiasts, I spent a long time roving the plains and peaks of Hyrule as it appears in Breath of the Wild – to the point where I was pretty confident I'd had my fill of this space when Tears of the Kingdom rolled around in May. We knew going into the sequel that it'd revisit The Great Plateau among many other familiar settings from the first game, but how much time we'd spend retracing our steps remained, ahem, up in the air. The answer was quite a bit, but I'm now dozens of hours into my first playthrough of Tears of the Kingdom and haven't once felt bored doing so.

Tears of the Kingdom is set several years after the events of the first game, and it's the little changes that indicate the passing of time that've helped my return to this world feel fresh. Certain areas that were once well-kept are now overgrown, for example; while other portions of the map that were once barren are littered with green shoots and signs of growth. In Breath of the Wild, the roads in Castle Town were covered in potholes, but these have now been smoothed over – presumably fixed by the locals since our last visit – whereas access to Death Mountain, the Akkala Citadel, and the multitude of overworld caves that have popped up in the interim are a direct result of The Upheaval.

Which is to say: I love how much care has gone into making things make sense in Tears of the Kingdom, even if that's on a superficial level. Shaking up item and enemy placement in the game's most familiar areas galvanizes the lore justifications outlined above – in the same way similarly designed PC mods continue to evolve the likes Dark Souls and Elden Ring – and having random NPCs remember you after a single innocuous Breath of the Wild exchange never gets old.

Granted Zelda games have always incorporated degrees of backtracking – Ocarina of Time has four different versions of the same overworld (day and night across two timelines); whereas the Metroidvania-like structure of Link's Awakening makes backtracking essential in parts – but in Tears of the Kingdom doing so almost always feels like a necessity, not just as a means of progressing a video game story.

Sign up to the GamesRadar+ Newsletter

Weekly digests, tales from the communities you love, and more

"The biggest compliment I can pay backtracking through Breath of the Wild's old locales in Tears of the Kingdom isn't a comparison to an almost 20-year-old linear horror game, then, it's that it never feels forced."

To this end, coming at old landmarks from new directions, or passing through once important areas that are no longer the focus of your journey enriches the credibility of the world – better than any sequel to my mind that's tried the same in the past. The likes of BioShock, BioShock 2, and BioShock Infinite's trips to Rapture, for example, feel like separate and distinct variations of the same setting. In Dead Space 2, we revisit the USG Ishimura, but it's hardly the same following the first game's' cataclysmic finale. Dark Souls 3's reinterpretation of the first game's Anor Londo serves to underline the warped universe's penchant for repeating itself; and while returning to Resident Evil 2's RPD HQ in RE3 is cool, it has also always felt forced to me.

The biggest compliment I can pay backtracking through Breath of the Wild's old locales in Tears of the Kingdom isn't a comparison to an almost 20-year-old linear horror game, then, it's that it never feels forced. But I nevertheless think that comparison with Silent Hill 4, no matter how personal it is to me, is a valid one. Backtracking in games, no matter the genre, the console cycle, or the narrative reasons for doing so, quite simply, can ruin a perfect game.

Many people believed Breath of the Wild was perfect at launch six years ago. Tears of the Kingdom may not have hit the same heights critically, it may not be as revolutionary as its forerunner, but I do reckon it's handled a controversial world-building design decision with perfection.

Here are some of the best games like Zelda that are full of exploration and adventure

Joe Donnelly is a sports editor from Glasgow and former features editor at GamesRadar+. A mental health advocate, Joe has written about video games and mental health for The Guardian, New Statesman, VICE, PC Gamer and many more, and believes the interactive nature of video games makes them uniquely placed to educate and inform. His book Checkpoint considers the complex intersections of video games and mental health, and was shortlisted for Scotland's National Book of the Year for non-fiction in 2021. As familiar with the streets of Los Santos as he is the west of Scotland, Joe can often be found living his best and worst lives in GTA Online and its PC role-playing scene.